The Hubble Space Telescope may have solved the mystery of the curiously dimming star Betelgeuse, according to new research.

And to add even more intrigue to the story, the star appears to be dimming again, which is unexpectedly early based on what astronomers know about the star.

The study published Thursday in The Astrophysical Journal.

Betelgeuse is a nearby, aging red supergiant star in the Orion constellation about 725 light-years away. It’s one of the brightest stars in our sky.

As the star burns through fuel in its core, it has swollen to massive proportions. If it were at the center of our solar system, instead of the sun, the star’s outer surface would go beyond Jupiter’s orbit.

The star has fascinated astronomers for a long time. Because they’ve observed it so much, the scientists expect it to go through a dimming and brightening cycle every 420 days.

But Betelgeuse caught the attention of astronomers around the world in the fall of 2019 when it began to dim unexpectedly and continued through February. But then, its brightness dipped by two-thirds and the change was visible to the naked eye.

It was the faintest the star had been since measurements of it began 150 years ago.

Astronomers thought it might signify that Betelgeuse may be about to explode in a supernova and continued observing the star. It returned to its normal brightness by April. So, what happened?

The Hubble Space Telescope observed Betelgeuse in ultraviolet light beginning in January 2019, so it was able to contribute information for the star’s time line leading up to its dimming event.

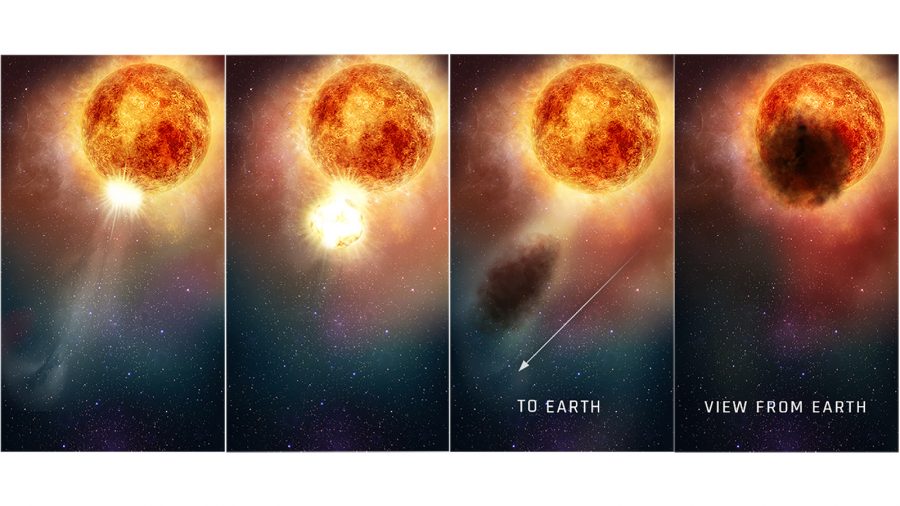

Astronomers looking through the Hubble data saw dense material that had been heated moving through the star’s atmosphere in fall 2019, from September to November. Hubble clocked the material moving at 200,000 miles per hour. In December, observations provided by ground-based telescopes revealed the star experienced a particular dip in brightness concentrated in its southern hemisphere.

The superheated plasma was released from the star through a large convection cell, like hot bubbles rising in boiling water—except hundreds of times the size of our sun.

When the star ejected this large amount of hot material comprised of gases, the material cooled as it reached the star’s outer layers and formed a dust cloud that blocked starlight from about a quarter of the star’s surface.

“With Hubble, we see the material as it left the star’s visible surface and moved out through the atmosphere, before the dust formed that caused the star to appear to dim,” said Andrea Dupree, lead researcher and associate director of The Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian, in a statement. “Only Hubble gives us this evidence of what led up to the dimming.”

What’s Next for Betelgeuse?

Hubble has been used to analyze Betelgeuse as part of a three-year study using the telescope to study how the star’s outer atmosphere varies. Hubble’s ultraviolet capability allows it to see the hottest layers of the star, which can’t be seen in visible light. These layers exceed 20,000 degrees Fahrenheit.

Astronomers are unsure what caused the ejection of the star’s material in the first place, but it may have had something to do with Betelgeuse’s normal cycle of dimming and brightening, which is called pulsating. But the way Betelgeuse is losing material, including the loss of two times the normal amount of material coming just from its southern hemisphere, is unusual.

“All stars are losing material to the interstellar medium, and we don’t know how this material is lost,” Dupree said. “We know that other hotter luminous stars lose material and it quickly turns to dust making the star appear much fainter. But in over a century-and-a-half, this has not happened to Betelgeuse. It’s very unique.”

When Betelgeuse moved out of Hubble’s view, astronomers used NASA’s Solar TErrestrial RElations Observatory spacecraft, or STEREO, to keep an eye on its brightness. And observations from this summer show the star is experiencing unexpected dimming again.

“Betelgeuse typically goes through brightness cycles lasting around 420 days, and since the previous minimum happened in February 2020, this new dimming is over a year early,” Dupree said.

Some astronomers speculate that the star’s behavior is a precursor to a supernova.

Betelgeuse will eventually end its life and explode in a supernova—even if it doesn’t occur during our lifetime. Astronomically speaking, however, given the distance of the star, this current dimming event happened in 1300—but we’re only able to observe these changes to the star now.

Dupree and her fellow scientists will observe Betelgeuse more in late August and early September.

“No one knows how a star behaves in the weeks before it explodes, and there were some ominous predictions that Betelgeuse was ready to become a supernova,” Dupree said. “Chances are, however, that it will not explode during our lifetime, but who knows?”