Jiang Zemin’s days are numbered. It is only a question of when, not if, the former head of the Chinese Communist Party will be arrested. Jiang officially ran the Chinese regime for more than a decade, and for another decade he was the puppet master behind the scenes who often controlled events. During those decades Jiang did incalculable damage to China. At this moment when Jiang’s era is about to end, Epoch Times here republishes in serial form “Anything for Power: The Real Story of Jiang Zemin,” first published in English in 2011. The reader can come to understand better the career of this pivotal figure in today’s China.

The full series is available here.

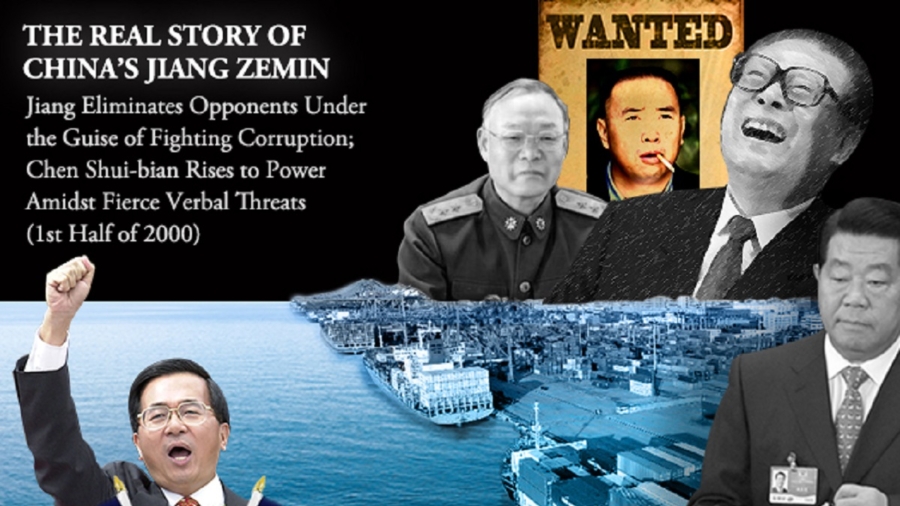

Chapter 15: Jiang Eliminates Opponents Under the Guise of Fighting Corruption; Chen Shui-bian Rises to Power Amidst Fierce Verbal Threats (1st Half of 2000)

Under Jiang Zemin’s reign, corruption throughout the bureaucracy reached unprecedented levels.

He actually found it desirable to rule China with corrupt officials. Winning the allegiance of others always banks on something. Some rely on their wisdom and prestige, others count on popular election. As such Jiang, lacking wisdom and not having been elected, knew that were he to appoint honest and upright officials his incompetence and corrupt ways would be noticed. How Jiang treated Zhu Rongji, who was widely known as an official of integrity and meritorious service, was a telling sign of what kind of officials Jiang was looking for. Corrupt officials, by contrast, were advantageous for Jiang in that they wouldn’t pose a threat—they were disdained by the public.

Ironic it is that corrupt officials have been among the most vocal in China’s fight against corruption. All of the senior officials who fell from power—on charges of graft—in internal political struggles were those who had given strong support to “anti-corruption initiatives.” Jiang, himself the head of arguably China’s most corrupt family, used slogans related to “fighting-corruption” as a means to win popular support and attack political opponents. In Robert Kuhn’s biography of Jiang remarks about fighting corruption abound, though. But actions count louder than words. All of the corrupt officials loyal to Jiang met with swift promotion while those who held different political views were punished cruelly, usually under the guise of “fighting graft.” Others who were useless to Jiang similarly met with punishment, as a warning to others.

In 2000, in the public’s eye, Jiang seized upon the opportunity provided by what has become known as the “Yuanhua Case” to eliminate political opponents and protect those loyal to him. The telling episode deserves discussion.

1. The Startling Yuanhua Smuggling Case

The “Yuanhua case” has a long story behind it. The main culprit of the case is the board chairman of the Yuanhua Group, Lai Changxing. Lai founded the group in 1994 and was thereafter engaged in the practice of smuggling. According to official sources, from 1996 up through the time the case came to light, the Yuanhua group was engaged in some five years of illicit smuggling. The value of goods smuggled by the group totaled 53 billion yuan (US$6.4 billion), with duty fees evaded amounting to 30 billion yuan (US$3.6 billion); this resulted in a loss of 83 billion yuan (US$10 billion) in revenue for the state. At the time the Yuanhua case was regarded as the largest incident of smuggling to have taken place since the CCP came to power in 1949.

Although the Yuanhua smuggling case was widely reported in Hong Kong and Macao, media in China didn’t report on the affair whatsoever, save for marginal mention in one November 1999 Beijing Evening News report. The case began to gain attention in 2000 after being reported on widely by international media such as The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, The Washington Post, and The L.A. Times.

According to coverage of the case, the matter came to light via an anonymous tip-off that then-premier Zhu Rongji received in March 1999. The source exposed the details of the massive smuggling that the Yuanhua group was carrying out in Xiamen City. The source provided detailed eyewitness testimony and physical evidence. It was in this fashion that the major smuggling case and the astronomical figures it involved came to light.

Regarding this case, Zhu Rongji said, “No matter who is involved, it should be thoroughly investigated regardless of his status.” Jiang chimed in along similar lines, saying that those involved should be punished heavily irrespective of their status. Jiang’s position on the case changed quickly, however, when the investigating task force discovered that the matter was closely connected to Jiang’s subordinates, among whom were Jia Ting’an and Jia Qinglin.

In early 2000, the Hong Kong Economics Times quoted an informed source in Beijing as saying that the 420 Investigation Task Force—the group appointed by the Central Committee of the CCP to investigate the Yuanhua case—was required to complete its investigation before the Two Conferences (the National People’s Congress and the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference) were convened. The stipulation was in place so that authorities could publicize at the two conferences their “significant accomplishments” of fighting graft in what they called “a century-spanning campaign against graft.” The proviso showed that what was really central for Jiang was seizing the occasion of the Yuanhua problem to boost his own standing. At the same time, though, Jiang wished for swift closure to the investigation in that he feared being implicated.

Executing Accomplices Before the Case Was Closed

Multiple departments conducted a joint investigation into the Yuanhua matter in 2000, with involved bodies including the disciplinary inspection committee, supervision department, customs authorities, public security department, prosecutor’s office, court, and finance and taxation units. The smuggling in Xiamen City and the involved dereliction of duties were investigated thoroughly. During the investigations over 600 persons were probed, with nearly 300 being prosecuted in the end for criminal liability.

In 2001 courts at several levels issued a total of 167 verdicts on 269 defendants in connection with the Yuanhua smuggling case. In July, before the case was closed, several persons had already been sentenced to death and executed. Victims included Ye Jichen, the former president of the Xiamen branch of the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China; Wu Yubo, the former section chief of Ship Management section of the East Ferry Management Office of Xiamen Customs; along with Wang Jinting, Jie Peikong, Huang Shanying, Zhuang Mingtian, Li Baomin, and Li Shizhuan, among others.

In such a high-profile case, the execution of 10-plus accomplices before the conclusion of the investigation was tantamount to destroying evidence, making it impossible to ever truly solve the case. This owed fully to the case’s bearing on the close subordinates of Jiang Zemin, who acted as quickly as possible to wipe out sources of incriminating evidence. The acts of killing, disturbing as they were, were in fact then turned around by Jiang and made out to be signs of the Party chief’s strong “determination” and a mark of achievement. Media widely reported the matter in a positive, affirming light.

Jiang Thanked Lai Changxin

During the investigation Jia Ting’an, who was one of Jiang’s most trusted confidants and the director of Jiang’s office, on one occasion divulged classified information to Lai Changxing. Lai also revealed that he was on very good terms with three of Jiang’s five secretaries, of whom one was Jia Ting’an, the chief secretary.

Many people aren’t familiar with who Jia Ting’an is. Jia was the director of Jiang’s office when Jiang became General Secretary of the CCP. He had before then been Jiang’s secretary when Jiang worked in the Ministry of the Electronics Industry. Jia returned to Shanghai with Jiang in January 1985, later coming back to Beijing with Jiang in June 1989. As Jia was Jiang’s most important secretary and assistant, people called him the “Master Secretary.”

In 2004 Jiang promoted Jia from the director of Jiang’s office to the director of the office of Central Military Commission (CMC). Jiang also recommended that Jia’s military rank be raised directly from that of a colonel to lieutenant general; Jiang’s invoked the pretexts of this being a “special circumstance” and of “benefit to our work.” Members of the CMC said that Jia’s administrative rank was merely that of a bureau director, of which the corresponding military rank is colonel, and that promoting Jia as Jiang had sought to do could result in a revolt in the Commission. Jiang nonetheless insisted on pushing ahead with the move. When Jiang made the recommendation a second time the motion was again tabled in a CMC meeting. The facts suggested that Jia was clearly Jiang’s most trusted subordinate.

Lai Changxing stated on one occasion that, “Jiang’s mansion was inside the Zhongnanhai compound. Jiang lived on one side while his security guards and secretaries occupied the other. Jiang mostly lived in Zhongnanhai, but when the mansion was under renovation in 1997 and 1998 he lived in Diaoyutai.”

When speaking with Sheng Xue, the author of The Dark Secrets behind the Yuanhua Case, Lai said that although he did not have direct contact with Jiang, he had once intended to make a donation to the CMC. Jiang’s secretary reported the matter to Jiang. Lai added, “Jiang said that I didn’t have to do so. He would like me to keep the money for business use. Jiang also expressed to me his appreciation. He knew that I was his secretary’s close friend.”

On one occasion when Jia went to the airport to pick up Jiang after Jiang returned from an overseas trip, Jia told Jiang that Li Jizhou (the former deputy minister of public security) was involved in an automobile smuggling case in Guangdong Province. Then Jia asked another of Jiang’s secretaries to ask Lai whether he was involved in the affair.

Lai elaborated, saying that the second secretary was Jiang’s family steward, and he took charge of everything in Jiang’s family. When asked by the second secretary, Lai replied, “I have absolutely nothing to do with that case.” The secretary said, “If you have nothing to do with the case it will be easier for them to deal with it.”

Afterwards Lai promptly told Li Jizhou about the matter while in Zhuhai City; at that time Li Jizhou was accompanying Zhu Rongji to inspect efforts meant to combat smuggling in Guangdong Province. Along with this Lai made plans to help Li’s girlfriend, Li Shana—a former official at the Ministry of Public Security’s Transportation Department—hide and avoid capture for her involvement, though she was later arrested.

Given that Lai’s relationship with Jia was that close, could one really expect Jiang to bring Lai to justice? As lofty as Jiang may have pitched his anti-corruption rhetoric, his crime fighting campaign was merely a veneer by means of which he could attack his political opponents.

Attacking Ji Pengfei and Liu Huaqing

In the then-sensational Yuanhua case, Jiang’s real targets were Ji Shengde, son of the senior diplomat Ji Pengfei, and Liu Huaqing’s daughter and daughter-in-law.

Jiang is so narrow-minded that he was sure to take revenge on those who verbally made light of him. Two figures were always on his mind: one was Ji Pengfei and the other Liu Huaqing. Both of them had networked with people extensively in their respective fields, but neither cared much about Jiang. Of course, little could two senior figures such as they be blamed for a lack of respect toward the appointed “core” leader. The fact was, Jiang was mediocre and incompetent, skilled at little.

Ji Pengfei was once a heavyweight in China’s foreign affairs system, a key figure in the hand-over of Hong Kong’s sovereignty. He used to hold high-ranking positions, of which were included Deputy Premier, Member of the State Council, Director of the Office of Hong Kong and Macao Affairs, Vice Chairman of the National People’s Congress, and Member of the Standing Committee of the Central Advisory Council. Before China opened up to the world, his grandson used to dress in fashionable clothes brought back from overseas and was always in the limelight. Jiang was nothing to Ji. Ji’s son, Ji Shengde, never had anything good to say about Jiang. All of this made Jiang boil beneath the surface. Ji Shengde, who was Ji Pengfei’s only son, was the Deputy Director of the Intelligence Department of the People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) Headquarters of the General Staff. He was on close terms with Lai Changxing. Meanwhile, Liu Huaqing’s daughter was a subordinate of Ji Shengde. This resulted in the two being attacked by Jiang in unison.

In mid March 1999, during which Ji Shengde was in Zhuhai City, he was asked to rush back to Beijing to attend an expanded meeting of the CMC. As soon as he arrived at the conference room, Ji sensed that something was awry. Nobody greeted him. He was then promptly arrested and it looked as if he would be sentenced to death. After his arrest Ji’s father, Ji Pengfei, who was spending his retired life in Xiangshan (a vacation resort near Beijing), wrote Jiang and other top leaders four times, asking Jiang to spare his son the death penalty. The request was rejected. In despair Ji Pengfei committed suicide by swallowing sleeping pills at 1:52 p.m. on Feb. 10, 2000.

With regard to father Ji’s death, the state’s official mouthpiece, the Xinhua News Agency, carried only a brief news item on the matter. Jiang didn’t attend the funeral service. The CMC, the four military departments, and the Ministry of Defense didn’t even send a funeral wreath. With the help of a few retired senior officials and/or their widows, Ji’s widowed wife, Xu Hanbin, was able to hold off her son’s execution for the time being.

After attending his father’s funeral service, Ji Shengde, who was kept in custody at the PLA’s Department of General Staff, felt even more hopeless than before. He attempted to commit suicide himself by slitting his wrist with a toothbrush handle and swallowing more than 70 sleeping pills. The suicide attempt failed, however. Xu Hanbin asked Jiang to grant Ji Shengde medical parole on account of hypertension, but the request was rejected. She then asked for permission to visit Ji three times a week and send meals without restriction. Her request was again rejected. Unable to stand the grief and indignation from this, Xu attempted to commit suicide by swallowing sleeping pills on the evening of Sept. 14, 2001. Xu was rushed to Hospital 301 and rescued, however. Incredibly, Jiang wanted to see destroyed members of a family such as this that had dedicated their lives to the CCP.

As to Liu Huaqing, a former member of the Standing Committee of the Central Politburo and Vice Chairman of the CMC, Jiang had long wanted to remove him from the political arena. Jiang had a hard time finding a proper opportunity. Liu was Jiang’s military “mentor,” the man assigned by Den Xiaoping after the Tiananmen Massacre on grounds that Jiang had never served in the military. But Jiang, someone who promoted generals on a whim, definitely didn’t want anyone giving him constant direction.

After the Tiananmen Massacre in 1989 Deng had appointed Jiang as the General Secretary of the CCP Central Politburo and Chairman of CMC. In light of the fact that Jiang lacked military experience, Deng made a point of assigning two senior generals—Liu Huaqing and Zhang Zhen—as Vice Chairmen of the CMC so that the two could assist Jiang and maintain morale in the military.

After gradually becoming a full-fledged General Secretary, Jiang began to develop his own faction in the military; his means was, as discussed earlier, offering special promotions to young and middle-aged generals. Shortly thereafter Jiang changed his style of non-intervention in military affairs to one of more active involvement. Liu Huaqing and Zhang Zhen expressed discontentment over Jiang’s intervention, insisting that the troops should be led by those with military acumen. One source has even claimed Liu was seen pointing his finger at Jiang in a Politburo meeting, scolding him. Liu took it for granted that he was senior to Jiang, given Deng’s appointment of Liu. But little did Liu realize Jiang was the kind of person who never forgot or forgave any slight.

In 1999, on the occasion of the PRC’s fiftieth anniversary, Jiang ordered that no retired generals should wear military uniforms at the celebratory events. He did this so as to make himself more attention grabbing. Before reviewing the troops, Jiang went up to the rostrum overlooking Tiananmen to greet senior Party, government, and military officials. As soon as Jiang spotted Liu, donning a general’s uniform and making for an awesome presence, he felt that Liu was willfully challenging his personal authority. Jiang confronted Liu, his anger veiled, “Didn’t I say that it’s forbidden to wear the uniform? What’s the matter with you?” Liu didn’t buy it and came back, “You get to wear the uniform without having taken part in a single battle. Then why can’t I wear my uniform?”

Jiang’s anger was such that he was at a loss for words. His face reportedly turned pale and his body quivered with anger. It was not until Jiang was asked to ride on the vehicle from which he would inspect the troops that he calmed down. After the review of the troops Jiang told You Xigui, his bodyguard, that he would teach Liu Huaqing a stern lesson.

Zhang Zhen announced his retirement after the 15th National Congress of the CCP. Deng Xiaoping had passed away by this time, and Jiang was growing more and more powerful in the military after some painstaking, cunning maneuvering. Jiang felt that the time to teach Liu a lesson had arrived. But Jiang couldn’t find fault with Liu. At the time Liu’s daughter, Liu Chaoying—herself a colonel and the Deputy Director of the Fifth Intelligence Division of the PLA’s Department of General Staff—was involved in a scandal involving illegal campaign contributions in the U.S. As Liu Chaoying’s direct supervisor happened to be Ji Shengde—a close friend of Lai Changxing—Jiang saw the campaign fiasco as a wonderful chance to take action.

When Lai Changxing described to Sheng Xue, the author of The Dark Secrets behind the Yuanhua Case, his relationship with Ji Shengde, he said, “No matter whether I was in Beijing, Shenzhen, Xiamen or Hong Kong, he would definitely come to see me as long as he was around. We’ve met up countless times.” Attacking Lai was not Jiang’s real aim. His actual targets were Ji Shengde and Liu Huaqing’s daughter.

Liu Huaqing’s youngest daughter, Liu Chaoying, and his second daughter-in-law, Zheng Li, were the two people Liu loved most dearly. He could hardly take food or rest well after the two were arrested. After turning the matter over in his mind, Liu concluded that he had no choice but to pluck up his courage and intercede with Jiang. But Jiang uttered not so much as a word after receiving a call from Liu about the matter. Jiang’s countenance even revealed a hint of satisfaction after hanging up the phone. Zeng Qinghong had once told Liu, “We can’t stop you from opposing Chairman Jiang, but it’s nothing for us to arrest your daughter-in-law, your wife, and your daughter.”

Liu’s daughter-in-law, Zheng Li, was an officer of the General Political Department of the PLA. After her arrest she was watched by two female soldiers day and night. She once escaped from custody while going to the restroom. When she arrived in Henan Province she called Liu, asking him if he knew of her arrest. When Liu answered that he did know, she realized that nobody could really help her. She then turned herself in to the Central Investigation Department.

When Liu’s daughter, Liu Chaoying, was arrested at a VIP lounge of the Beijing International Airport, she protested with pride, “I am Liu Huaqing’s daughter, how dare you arrest me!” The 10 some soldiers didn’t listen to her. They whisked her off from the airport without saying a word. As Liu Chaoying was arrogant in custody and refused to make a “confession,” an investigator slapped her and verbally abused her. She then realized the gravity of the situation, for she had never been treated in such a manner. She thus began to divulge information.

Jiang personally oversaw all handling of the Liu family’s case, giving in fact direct commands and supporting the investigators. After Liu’s family members were arrested it was said that somebody close to Jiang had once advised, “Give leniency to the descendants of those who have helped you.” In other words, Liu deserved credit for the assistance he had given Jiang over the years. Jiang was furious at the suggestion, however, and told the person to be silent.

The Yuanhua Case Embroiled Jia Qinglin

Jiang’s trusted subordinate Jia Qinglin was another major figure in the Yuanhua case.

The size and scope of the Yuanhua case in Xiamen City, which came to light in 1999, surpassed all other corruption and smuggling cases known to China since the founding of the PRC in 1949; funds involved in the case totaled around 70 billion yuan (US$8.4 billion). More than 250 local, provincial, and even central CCP officials were embroiled in the fiasco. Persons involved were accused of accepting bribes of as much as hundreds of millions of U.S. dollars over a period of five years—1994 through 1999. Products worth hundreds of millions U.S. dollars—including automobiles, fuel, raw materials, heavy machinery, and luxury goods—were smuggled into China through the Xiamen port. From 1994 to 1996 Jia Qinglin was the Party Secretary of Fujian Province and the Director of the Standing Committee of the Fujian Provincial People’s Congress. This is the reason Jiang didn’t allow the investigation of the Yuanhua case to go beyond a certain level of the hierarchy.

Jia Qinglin was born in Hebei Province in March 1940. He once worked in the same First Machinery Department that Jiang once did. The coincidence won him the appreciation of his former superior, Jiang. As Jiang was incrementally promoted toward the post of General Secretary, Jia’s political outlook improved as well.

After Jiang ousted Chen Xitong, the Party Secretary of Beijing, in 1996, Jia Qinglin was promoted first as the Mayor of Beijing and later Party Secretary of Beijing and even given membership in the Politburo. Jiang obviously thought highly of Jia.

After graduation in 1962 from the Department of Electrical Power of the Hebei Institute of Engineering, Jia Qinglin found work in the Policy Research Office of the First Ministry of Machinery Industry. In 1978 he was appointed General Manager of the China National Machinery Import and Export Corporation. He relocated to Fujian in 1985 and was promoted to Provincial Governor of Fujian in early 1993. In late 1993 he was appointed Party Secretary of Fujian Province.

After the Yuanhua case surfaced, the investigation task force ferreted out a group picture of Lai Changxing and Jia Qinglin taken when Jia visited the Yuanhua Group. Lai said that the investigation task force wanted to arrest him, and that if he were captured and were to reveal Jia Qinglin, Jia would be finished politically. Thus when Jia Qinglin was promoted, a jingle could be heard in Fujian that went, “A crooked official from Fujian has gone on to become a big gun in Beijing.”

In 2003 four deputy secretaries of the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection asked the Party Central Committee to reinvestigate the political qualifications of Jia Qinglin. On top of a variety of officials, including some from the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC), opposing Jia’s appointment to Chairman of the CPPCC, the Audit Office of the State Council exposed a massive financial scandal related to Jia when he held official posts in Fujian.

The Audit Office, which was close to the expiration of its office term, submitted an audit report in late January 2003 to the Politburo of the CCP Central Committee and the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress; the report was in regards to national debt related to special construction funds. The report revealed that the construction of the Changle International Airport in Fuzhou City (of Fujian Province), of which the original budget, as authorized by the Fujian CCP Provincial Committee in 1993, was in total 2 billion yuan (US$240 million), had in fact already overspent 1.2 billion yuan by early 1997. Between 1993 and 1997, when Jia Qinglin was the Provincial Governor and Secretary of CCP Provincial Committee in Fujian, he took over and redirected construction funds slated for the Changle airport. According to investigations, fully 1.28 billion yuan had been misappropriated by the Fujian CCP Provincial Committee and Provincial Government. The majority of the funds were either used on perks for high-level officials or could not be traced. By the time construction of Changle airport was completed and operations began in early 1998, the accumulated financial losses for the first five years reached a staggering 1.55 billion yuan (US$186 million). The primary source of losses was the bloated scale of construction. The quantity of travelers and freight have only reached 30 percent of design capacity. The construction cost of the airport stands one and a quarter times that of equivalent scale airports in China. It is said that Audit Office’s report further revealed that Jia Qinglin and He Guoqiang authorized 11 times the use of a special national fund in order to cover the 1.2 billion yuan in excess expenditures.

The Audit Office also verified that part of the funds embezzled in the name of airport construction was actually diverted to build or purchase 570 luxury villas in the cities of Fuzhou, Xiamen, Zhuhai, Dalian, Qingdao, Wuxi, Hangzhou, and Beijing. The villas were quickly snapped up by 230 unnamed senior CCP officials.

In the Audit Office’s report on national debt for special construction funds dated December 2000, mention was made of “serious fund embezzlement, overspending, and unknown disposition existing in the four major development projects, of which are included airport construction, highway construction, the Three Gorges project, and comprehensive agricultural development.” The report clearly indicated that the projects handled by Jia and He—referred to as the “false and disastrous” (homonyms for “Jia” and “He”) project—were plagued by embezzlement and unaccounted for capital expenditure.

When the report was sent to Jiang for review he made only brief comments, saying, “Problems similar to those involving the Changle airport are pretty common. These problems arose because of poor management.” The report was then returned to the State Council.

When Jia Qinglin served as the Party Secretary of Fujian Province, his wife, Lin Youfang, was the Party Secretary of the China Foreign Trade Group in Fujian. She was accused of serious corruption in connection with the Yuanhua case and could never shake the accusations. Jiang thus asked Jia to divorce her in 2000 so as to make clear Jia had “drawn the line” between he and Lin.

However, Lin openly denied reports of her divorce. She said, “We have been married 40 years. Our relationship is excellent and we have a happy family.” She also pointed out, “I have never heard of this so-called ‘Huayuan Company’ that’s registered in Hong Kong.” What she said was partly true, in that the company involved in the smuggling was the “Yuanhua group” of Xiamen City, not the “Huayuan Company” of Hong Kong. However, sources in Fujian Province revealed that Lin was in fact in charge of Fujian’s foreign trade and that it would take a fool to believe she didn’t know about the Yuanhua group; the group was the largest import and export company in Fujian. Her pleading innocence only worsened an already bad situation.

Whether Jia and Lin ever got divorced is still to this day unknown. However, in an official photo taken at a dinner party Jia hosted in honor of Lian Zhan on April 28, 2005, Lian’s wife, Fang Yu, is standing beside Lian while Jia’s wife is nowhere to be seen. On Sept. 18, 1999, Jiang Zemin made a point of supposedly “inspecting development work in Beijing” and attended public activities with Jia, who was facing impeachment at the time. Those not closely involved in the matter considered Jiang’s move to be a show of political backing for Jia.

As the 10th National People’s Congress and Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference were about to convene, Jia Qinglin, who had been unofficially slated, thanks to Jiang, to take the position of the chairmanship of the 10th Political Consultative Congress, submitted a letter of resignation from the Politburo, citing poor health. Jiang however rejected Jia’s resignation. Jiang said, “If you step down from the political arena, I am finished.” This suggests that Jiang must have been involved in illicit financial dealings as well. Jiang used Jia, and Jia in turn provided protection for Jiang. Their close connection can be made out.

According to one media report, the Beijing municipal government gave a banquet to celebrate Jia’s appointment as the chairman of the Consultative Congress. Throughout the banquet Jia kept silent and drank glass after glass of liquor. At one point he murmured to himself, “It’s not that I want the promotion…” In the meetings of the 16th National People’s Congress in November 2002, one picture, capturing a dispirited Jia sitting at his table, told what Jia felt inside: he had no choice but to be Jiang’s accomplice.

Although Jiang succeeded in promoting Jia to the highest circles of power in the CCP, the Yuanhua case still haunts and undermines Jia. Jia’s connection to the Yuanhua case has become a typical example of corrupt CCP politics. It is a constant, stark reminder of just how hollow Jiang’s talk of fighting corruption really is. Jiang intended to use the Yuanhua case to knock off political opponents, but ultimately ended up shooting his own foot.

2. The Death of Cheng Kejie

In 2000 when the investigation of the Yuanhua smuggling case in Xiamen was in high gear, Cheng Kejie, Chairman of Guangxi Autonomous Region, was executed.

Cheng was of a minority ethnic group, the Zhuang nationality. He at one time had worked as a technician, an engineer, a chief engineer, a deputy director, and then director, all at the Liuzhou Railway Bureau of Guangxi Province. He began his career at the bottom of the totem and made his way up in increments. In 1986 he became Vice Chairman of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region Government, and then, in 1990, its Chairman. In 1992, he was appointed as a member of Central Committee at CCP’s 14th National Congress. With his election to Vice Chairman of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress in 1998, Cheng became a Party and state leader equal in rank to vice-premier.

During his time as Chairman of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, Cheng had a mistress with whom he shared bribes of 41 million yuan (US$5.9 million). On July 31, 2000, Cheng was accused of “taking an enormous amount in bribes” and sentenced to death by the Beijing No.1 Intermediate People’s Court. His political rights were deprived for life and all of his personal property was expropriated. Cheng immediately applied for an appeal, but was turned down by Beijing People’s High Court. On Sept. 7, the Supreme People’s Court agreed that the Beijing High Court’s sentencing of capital punishment was in accordance with criminal law. On Sept. 14, the death sentence was carried out on Cheng by the execution squad of Beijing No.1 Intermediate People’s Court.

So it was that in the short span of just a month and a half a Party and state leader equal in rank to vice-premier came to be executed. Cheng became the highest ranking official to be executed—and in the shortest time, at that—under CCP rule for this offense.

On Sept. 21, a state newspaper editorial declared that Cheng’s execution was a warning to high-level officials that nobody, regardless of rank, is above the law. The editorial also said that, “The verdict on Cheng Kejie and the government’s pledge of thorough investigation into the Xiamen smuggling case show that the government meant what it said about fighting corruption.” However, the total sum Cheng had embezzled was nothing compared with that of Jiang Zemin’s corrupt son, Jiang Mianheng—”China’s No. 1 corrupt official,” as he is called.

In fact it was not on account of unpardonable crimes coming to light that Cheng was arrested. Rather, the collection of evidence only began after his arrest. And it resorted to terribly underhanded measures, no less. A little background is in order first. Cheng, who was a married man, fell in love with a married woman named Li Ping. In late 1993 Cheng and Li decided to divorce their respective spouses and marry one another. Cheng embezzled 4 million and prepared to move abroad with Li. It should be noted that investigators did not know this. Authorities only learned of these plans upon coercing Li into coming clean; police showed Li photos of Cheng mingling with other women. Li was overwhelmed with jealousy upon seeing the photos. Li thought that she had been deceived by Cheng all along, and thus revealed to police their entire plan. Cheng’s execution then quickly came about. It was only too late that Li learned she had been deceived: the photos she was shown were fake. Cheng’s face had been inserted into the photos with image-editing software. After realizing what had happened Li cried and screamed that it was she who killed Cheng.

Hardly has Jiang used legitimate means to root out corrupt officials. Behind the rogue-like investigations lies a dirty purpose. According to one source, the real reason for Cheng’s execution was that he had offended Jiang. Cheng once upon a time showed excessive “care” for Song Zuying, a representative of the National People’s Congress and a singer. It touched off Jiang’s jealousy and later resulted in Cheng’s death. Right through to his very execution Cheng had no idea who he had offended or who it was that was so bent on ending his life.

Why Cheng was quickly executed before the Yuanhua case trials has been a mystery to those not intimately involved with the situation. Even those in the inner circles of the CCP, including many people from the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection and the National People’s Congress, are puzzled by and wonder about what was behind the death of Cheng Kejie.

3. Taiwan’s Presidential Election

As soon as the year 2000 started, all of the Chinese media around the world focused their attention on the March presidential election in Taiwan. It was a fierce campaign among the political parties involved. The three major candidates were the chairman of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) Chen Shui-bian, the chairman of the People First Party James Soong, and the chairman of the Nationalist Party (KMT) Lien Chan. Polls indicated that Chen and Soong were neck-and-neck, with Lien trailing slightly behind.

Jiang was stupefied. He didn’t know how to deal with the Taiwan election, which was drawing international attention. He ordered the Central Propaganda Department to describe the DPP as a radical “Taiwan independence” camp and constantly attack them in the media, hoping to sway public opinion in Taiwan. The Taiwanese people didn’t buy it, however. The level of support Chen received remained high. Jiang didn’t know how he would respond if Chen were really elected. War wasn’t something Jiang wanted to launch; he trembled whenever he thought about it. On top of that, he was even more worried that senior military leaders might gain power through the war and undermine his military authority. On the other hand, if he chose not to go to war, what would he do about the nationalistic fervor he had stirred up? Given the nationalistic sentiment among the general public and the pressure with respect to the military, Jiang felt he had to at least appear tough. Jiang’s power might be jeopardized if he failed to handle the situation properly. He was overcome with trepidation every time he thought of the dilemma he had to confront.

On Feb. 1, the U.S. House of Representatives passed the “Taiwan Security Enhancement Act,” expressing strong concern regarding the potential war across the Taiwan Strait. Given that, he hardly dared to take a hard line. The fiasco he suffered during the 1996 military exercise in the Taiwan Strait, where a missile exercise meant to demonstrate Chinese military might was humiliatingly cut short by U.S. intervention, was still fresh in his mind. Dealing with foreigners was undoubtedly Jiang’s Achilles Heel—his spine would turn to jello upon being confronted by a foreign power.

As head of state, Jiang had to take a political stance regarding Taiwan’s election. Jiang chose, as in previous times, to make a political show of it.

On March 4, Jiang addressed the representatives at the 3rd Session of the 9th National People’s Congress in Beijing. He made sure to speak sternly, saying that he “would be forced to take decisive measures if Taiwan’s authority indefinitely refused to negotiate a peaceful settlement on the issue of reunification.” And he called upon the representatives to “take a firm stand on the issue of Taiwan and its implications on Sino-U.S. relations.”

Any perceptive person, however, could see that he was playing word games. The speech left him a lot of wiggle room. The statement contained the following: “If Taiwan’s authority indefinitely refuses to negotiate a peaceful settlement on the issue of reunification,” but at that point there was no definite indicator as to who would be Taiwan’s authority. No matter who was elected, the truth was, he would assert that he was Taiwan’s authority. So Jiang’s speech was equivalent to not taking any stance, a far cry from how the Chinese media spun his speech as being “absolutely against Taiwan independence.” Also, the term “indefinitely” is equivocal. How long is “indefinitely”? Years? Decades? In short, even if Taiwan refused to negotiate with respect to reunification during the years that remained in Jiang’s administration, that would not necessarily be an “indefinite” refusal to engage in peace talks. Jiang certainly left himself with plenty of backdoors.

But Jiang tried to make a show of strength. CCTV broadcasted a series called “Chinese Troops” during that period, which was a thinly veiled threat. Troops were mobilized toward the regions neighboring the Taiwan Strait, implying that war would be inevitable if Chen Shui-bian was elected. The public seemed on edge. However, permits were not granted when students from several universities in Beijing planned to stage demonstrations to express their dissatisfaction. The several small demonstrations that did take place were dispersed quickly. What Jiang was afraid of was that, once people were given an outlet for free expression, long-suppressed dissatisfaction would erupt. That would jeopardize the Communist government’s power, as well as Jiang’s position as General Secretary.

Whenever Jiang faced tough problems, he would think of Zhu Rongji, the man he was deeply jealous of but often felt powerless against. Jiang looked down upon Zhu’s lack of craftiness. And he knew when to use Zhu as his attack dog. The only thing that lessened Jiang’s jealousy and hatred of Zhu was the thought of exploiting him. At those times he would be secretly happy.

Since Zhu was in charge of the economy, he knew better than anyone else what China could really bring to bear and he really didn’t want to see a war take place across the Taiwan Strait. Zhu’s stance on Taiwan was moderate, even though he appeared to take a hard line.

Jiang pushed Zhu to hold a press conference on Wednesday, March 15, less than three days before Taiwan’s election was to be held. At the press conference, Zhu feigned anger and pounded the table with his fist. He warned in a very stern tone that those who supported Taiwan independence would find themselves in dire straits. He said the Chinese government would not tolerate any form of independence for Taiwan, and that this was non-negotiable. Zhu also said that the Taiwanese people were facing a critical choice at a historical moment, and that they should not make their decision rashly and find themselves unable to undo their actions. A Western journalist at the conference asked Zhu what actions China would take, and when, against Taiwan. Zhu dodged the question and simply replied, “You’ll see in a few days.”

Taiwan’s presidential candidates responded to Zhu’s speech in different ways. The two leading candidates both expressed objections to the speech.

DPP candidate Chen Shui-bian indicated at a campaign rally in Pingdong on the same evening that only the Taiwanese people had the right to choose Taiwan’s leader, and that the Chinese Communist Party had no such right. Chen asked, “Are we Taiwanese going to elect our own president or are the communist leaders going to appoint one for us!? Are we going to elect Taiwan’s future leader or have ourselves a chief executive of China’s special administrative region [like Hong Kong]!?”

On the same day, in front of the Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall in Taipei the independent candidate James Soong told his supporters that Taiwanese would not be intimidated by the threat of military force.

Another independent candidate, Hsu Hsinliang, indicated that Taiwan must take seriously certain parts of Zhu’s speech, but that other parts of the speech would definitely arouse resentment among Taiwanese. Hsu advised the Taiwanese not to respond to Zhu’s speech with emotion, and stated that he wanted to tell Zhu that one of the barriers to implementing the “one China” policy was the frequent threats from China.

Jiang didn’t expect Zhu’s speech to elicit such a strong negative reaction from the Taiwanese people. Many young Taiwanese were angry about the threatening speech. It ended up pushing the election in a direction that Jiang was trying to steer it away from. The matter of Taiwan’s merging with China or being independent from it is ideological in nature, and not something that can be forced down people’s throats. In his inaugural speech, Chen Shui-bian said something quite profound: “History has proven that war can only bring about more hatred and animosity. It will not help the development of bilateral relations. Ancient Chinese people emphasized the difference between a king and an overlord. They believed that a benevolent government would make ‘those who are close-by happy, and those who are far away want to come,’ and that ‘if the far-away people are unwilling to accept, then cultivate your own virtue to entice them.’ These old Chinese maxims are pieces of wisdom that will hold true everywhere in the world even in the next century.” These ideas stand in stark contrast to Jiang’s faith in power politics. Jiang utilized the Tiananmen massacre to rise up through the ranks of the Chinese communist government. What he puts his trust in is coercion and intimidation. He shows little respect for ancient Chinese wisdom.

On March 18, voters in Taiwan elected the opposition leader, Democratic Progressive Party chair Chen Shui-bian, as their new president. The vote put an end to a half-century of rule by the KMT. Chen won 39 percent of all votes, followed by James Soong’s 37 percent. KMT candidate Lien Chan received only 23 percent. Over 82.7 percent of eligible voters cast their ballots. There is no doubt that the Communist’s threatening of Taiwan voters and verbal attack on the DPP facilitated Chen’s election.

The lights were on throughout the night in Zhongnanhai immediately following Taiwan’s election. Jiang never imagined the more-conciliatory KMT would lose so badly or that the DPP could seize political power so easily. Jiang was so flustered that he yelled at his subordinates, denouncing them as incompetent. Later many tried to ascribe blame to Zhu Rongji. Zhu’s image suffered a big blow in the eyes of the Taiwanese people as well, what with him becoming a symbol for saber-rattling warmongers. Zhu ended up the figure hurt most by Jiang’s shenanigans.

Not only Jiang was shaken by the election’s outcome: the whole top echelon of the CCP was caught off guard and left stunned.

On the evening of March 19, 2000, the news anchorman of China’s official communist television news read with a somber intonation a statement by the Communist Central Office of Taiwan Affairs. He read, “We hope the newly elected DPP authorities will not go too far.” The vacuity of the statement indicated that the CCP was at a loss over what to do. They blundered in their appraisal of the will of the Taiwanese people.

The spokesman for China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Sun Yuxi, indicated in a press conference that Tuesday that China would “wait and see.”

Jiang came across as much more moderate compared with the tone of pre-election propaganda. He acted as if nothing had happened, as if he had never issued a tough speech prior to the election. Jiang seemed to have forgotten that it was he who tricked Zhu into playing the part of the villain earlier on. It now looked like it was Zhu who had made a ruckus over nothing. Zhu regretted deeply having been a pawn in Jiang’s game.

Several years later Lu Jiaping submitted a letter to the Communist central leadership, representatives of the National People’s Congress, and members of the National Political Consultative Committee. He revealed in the letter that Jiang had been two-faced in his tactics handling the Taiwan issue. Jiang pledged on the one hand to attack Taiwan, hoping to gain the trust of generals and troops and thus maintain his authority with the military. But Jiang meanwhile promised the president of the United States that the PLA wouldn’t attack Taiwan as long as the U.S. supported his continuing to hold the position of Chair of the CMC.

Jiang barked aplenty about taking military action against Taiwan, and even made gestures of attack on several occasions. But all of it amounted to posturing, ultimately. The reality was, Jiang was using Taiwan as a trump card. He would wave it whenever his power was threatened, pretending war was imminent and giving the troops a sense of importance. When things had passed he would put the card away and save it until the next crisis.

From The Epoch Times