If you’re going into a public restroom, you may want to take a quick step back after flushing, as the swirling water creates an invisible aerosol that will carry whatever pathogen may be residing in the toilet bowl up and into your nostrils.

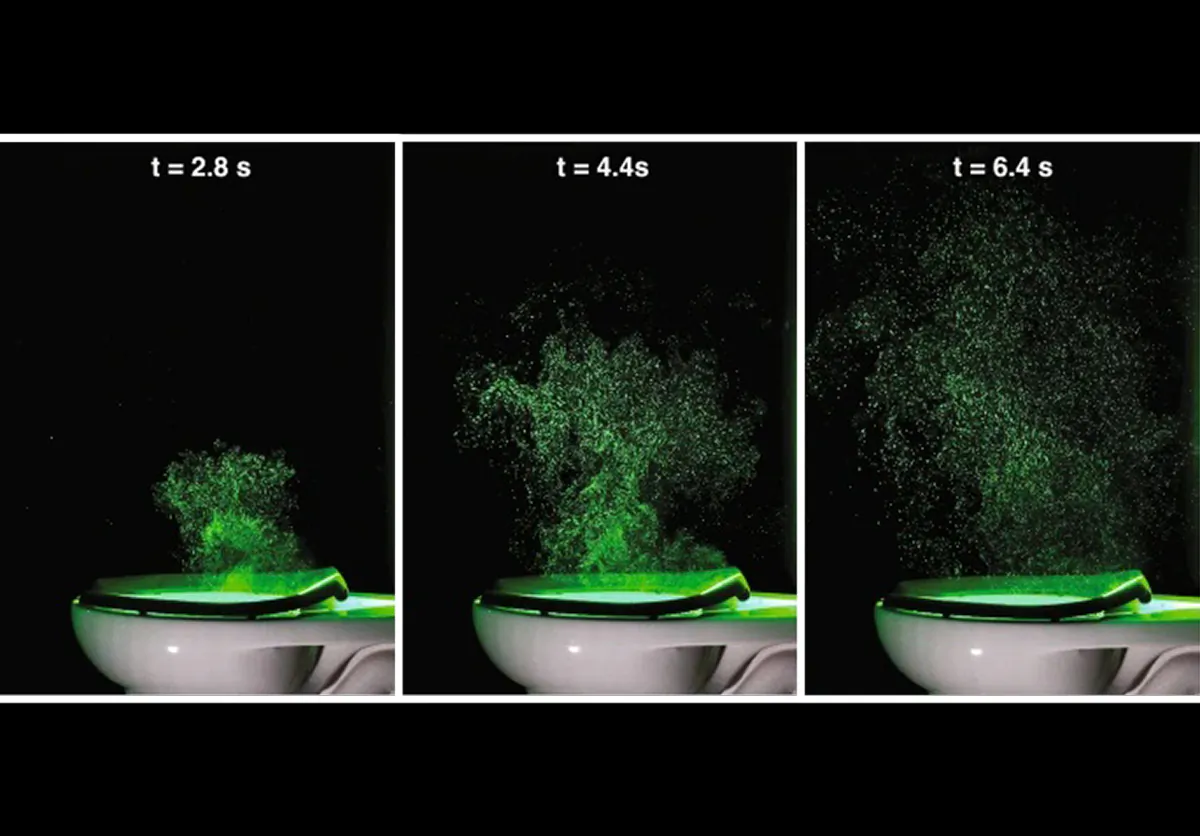

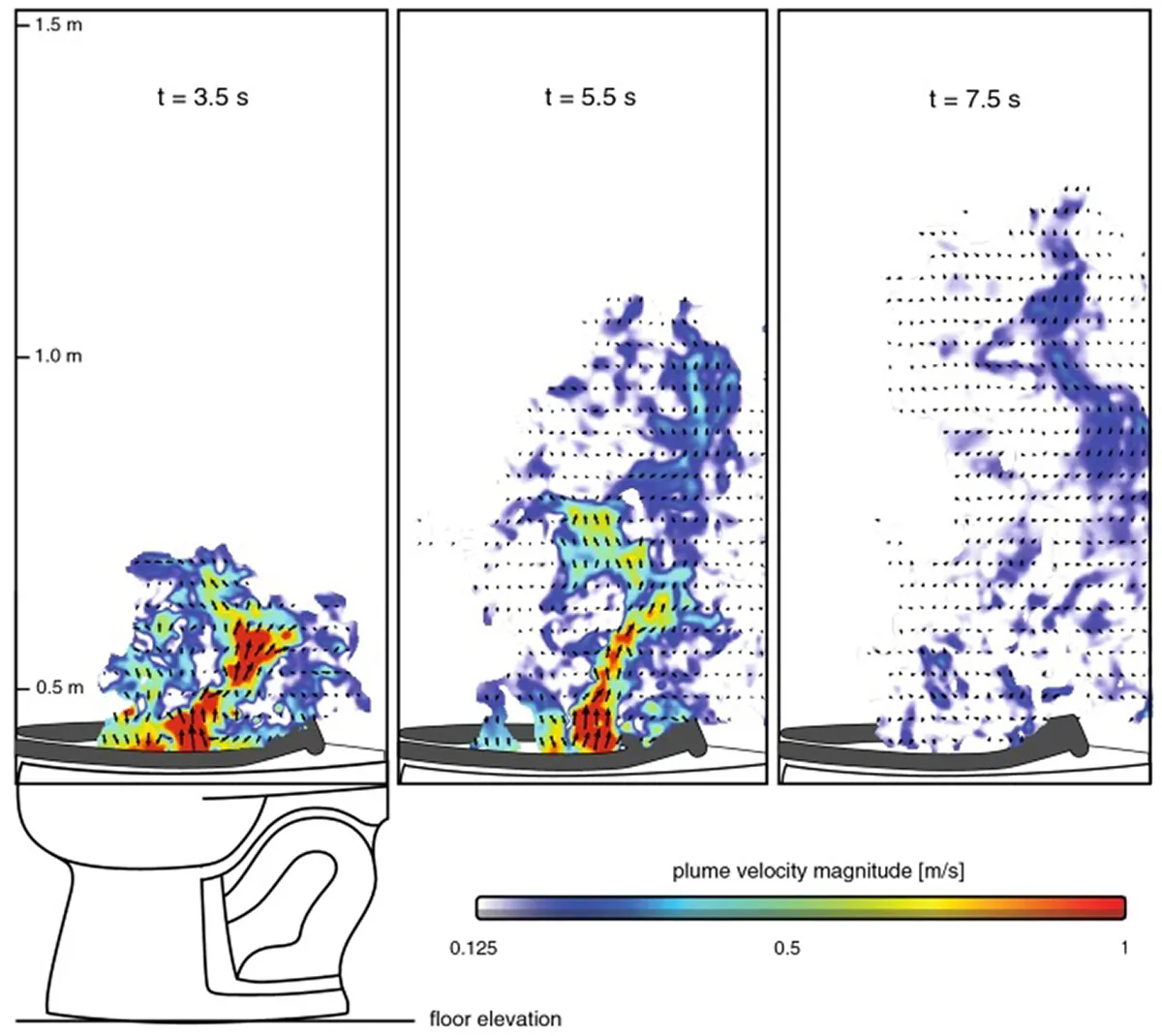

A study by a team from the University of Colorado Boulder, published in Nature near the tail end of the COVID pandemic, found that aerosolized plumes created by the flushing of a toilet can shoot up to five feet in the air from the toilet—reaching the height of an average adult’s face—within about eight seconds.

The study, headed by Professor John Crimaldi, mapped out the size and spread of toilet flush aerosols, which are known to carry pathogens.

For the study, they used a commercial 1.6 gallon-per-flush toilet, typical of those found across North America in public restrooms, mounted in front of a wall in an otherwise open laboratory space.

To photograph the aerosols after flushing, Crimaldi’s team used continuous and pulsed lasers to illuminate the airborne particles.

While the largest water droplets settle out within seconds, smaller aerosols remain suspended for much longer, and rise up fairly high.

“The rapid spread of the plume is facilitated by a strong unsteady jet that angles upwards and backwards towards the rear wall,” they concluded.

The team also measured the sound pressure level as an indicator of the strength and duration of the flush cycle, which they described as “chaotic in nature.”

Though the team used only clean water to chart the aerosol movements, they conceded that the presence of fecal matter and toilet paper “could alter plume dynamics in unpredictable ways.”

The researchers also said that “contamination of bowl water may persist after dozens of flushes.”

Closing the lid will prevent the aerosol plume from flowing up high, although not entirely, given that lids do not seal 100 percent.

That said, public toilets in the United States usually come without a lid, including those in many hospitals. A 2011 study published in the Journal of Hospital Infection advised against lidless conventional toilets to lower the risk of contamination.

The study specifically examined the extent to which toilet flush aerosols carry C. Difficile bacteria—the bacteria responsible for diarrhea—and tested air samples at various heights and locations, as well as surface samples.

Viruses, including COVID-19, have been shown to survive on surfaces for several days; others may survive much longer.

A 2008 study demonstrated that the influenza virus may survive on surfaces for up to four weeks; and HIV for up to eight weeks depending on the surface material.

Most common pathogens do not survive longer than a few days on most common materials, such as cloth or metal.