Eli Lilly and Co. announced on Wednesday that prices for the company’s most commonly prescribed insulins will be reduced by up to 70 percent later this year, a move praised by President Joe Biden, who urged other drugmakers to follow.

In a statement published on Mar. 1, the largest U.S. manufacturer of insulin said that it will cut the list price of its non-branded insulin to $25 a vial starting in May, making it “the lowest list-priced mealtime insulin available.”

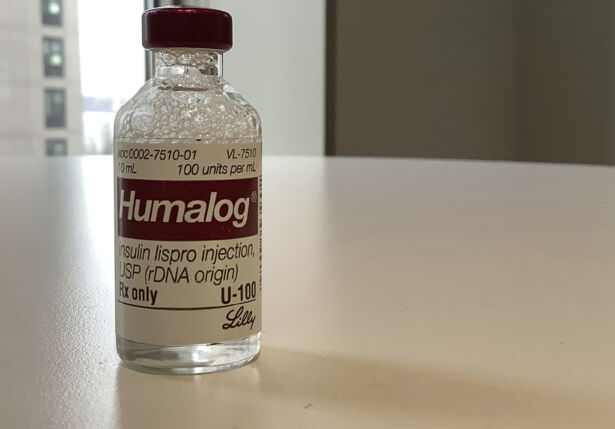

In the fourth quarter of 2023—which starts in October—Lilly will also reduce the list price for Humalog, the drugmaker’s most commonly prescribed insulin, and for another insulin, called Humulin, by 70 percent, the company said.

List prices are what a drugmaker initially sets for a product and what people who have no insurance or plans with high deductibles are sometimes stuck paying.

Starting in April, Lilly will also launch a basal insulin that is biosimilar, and interchangeable, with Sanofi’s Lantus. The new drug, called Rezvoglar, will be a less expensive version and may be substituted by a pharmacist without consulting the physician if the state’s pharmacy laws permit.

Rezvoglar can be purchased for $92 per five-pack of KwikPens, a 78 percent discount to Lantus, Lilly said.

“While the current healthcare system provides access to insulin for most people with diabetes, it still does not provide affordable insulin for everyone and that needs to change,” said Lilly CEO David Ricks.

Ricks said that it will take time for insurers and the pharmacy system to implement the drugmaker’s new prices, so the company will automatically cap out-of-pocket insulin costs at $35 per month for patients who have private insurance and use participating pharmacies.

The drugmaker noted that people without insurance can visit the InsulinAffordability.com website and “immediately download the Lilly Insulin Value Program savings card to receive Lilly insulins for $35 per month.”

The move, which Biden described in a statement on Wednesday as “a big deal,” comes amid criticism of health care companies and patient advocates who have long called for soaring prices of insulin to be reduced to help uninsured people who would not be affected by price caps tied to insurance coverage.

Last year, Biden signed a law, the Affordable Insulin Now Act, which is part of the Inflation Reduction Act, to limit the monthly cost of insulin to $35 for seniors.

“Today, Eli Lilly did that,” Biden said.

“For far too long, American families have been crushed by drug costs many times higher than what people in other countries are charged for the same prescriptions,” the president added. “Insulin costs less than $10 to make, but Americans are sometimes forced to pay over $300 for it. It’s flat wrong.”

Humulin and Humalog and its authorized generic brought in a total of more than $3 billion in revenue for Lilly last year. They rang up more than $3.5 billion the year before that.

Soaring Insulin Prices

Around 40 million Americans have diabetes, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and people with Type 1 diabetes must take insulin every day to survive.

According to the American Diabetes Association, more than eight million Americans use insulin. Some people who can’t afford their medication ration their insulin, which can result in hospitalization or death.

In 2020, the average senior paid about $54 per month for insulin, and some paid as much as $116 per month, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Over 21 million Americans, which is more than half of the nation’s diabetics, are under the age of 65, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Last August, Senate Republicans blocked a provision that would have also capped the cost of insulin at $35 for Americans on private health insurance, expressing hope that future federal and state legislation could offer that benefit.

In 2019 and 2020, more than 50 percent of insulin users with health insurance offered by employers on average exceeded $35 in out-of-pocket costs for a 30-day insulin supply, the Health Care Cost Institute reported.

The nonprofit group that tracks drug prices also said that around 5 percent of those people paid more than $200.

Jeff Louderback and the Associated Press contributed to this report.