While scanning samples of laser-mapped areas of the central Maya Lowlands, researchers discovered a large Mayan city, comprised of pyramids, plazas, and a water reservoir, hidden deep in the Mexican jungle. The discovery serves as confirmation that ancient civilization was widespread.

Tulane University doctoral student Luke Auld-Thomas and his advisor, Professor Marcello Canuto, found some 6,700 structures in a jungle near Campeche, Mexico, including a large city dating back nearly 1,500 years ago.

The city was named Valeriana.

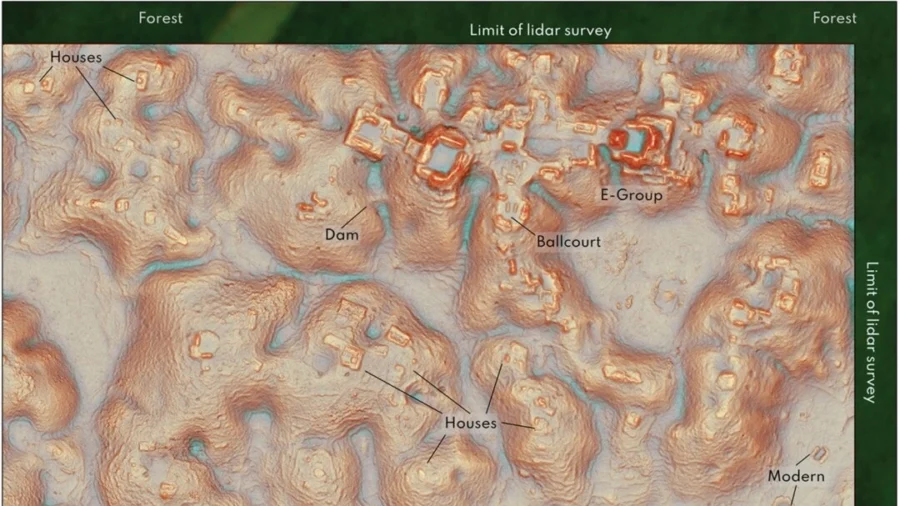

“The larger of Valeriana’s two monumental precincts has all the hallmarks of a classic Mayan political capital: enclosed plazas connected by a broad causeway; temple pyramids; a ball court; a reservoir,” the researchers wrote in their study, published Tuesday in the journal Antiquity.

Previously lost cities were stumbled upon by boots-on-the-ground archeologists, wading through dense and remote forests.

Recently, archeologists have been using Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) to map jungle areas, an aerial 3D mapping technique capable of scanning the surface underneath thick forest canopies.

Though highly efficient at detecting man-made surface structures, LiDAR remains expensive. Given that scientists have only examined areas expected to contain ancient ruins, questions arose regarding what extent this highly targeted mapping produces a distorted view of how dense and widespread ancient civilizations were.

Rather than look for fundraisers, Auld-Thomas decided to review LiDAR data collected over a decade ago, for completely unrelated purposes, by Mexican firm CartoData.

This gave Auld-Thomas and his team detailed topographic maps of 3 patches of land totaling 64 square kilometers, and three strips of land, 275 meters wide each and 213 kilometers long in total—another 58 square kilometers.

And sure enough, they found more than just a lost city; in fact, the dense jungle of Campeche was once a relatively densely populated and extensively engineered landscape.

“We can only conclude that cities and dense settlement are simply ubiquitous across large swaths of the central Maya Lowlands,” the research team concluded in the study.

According to the team, previous on-site validation proved that the number of buildings identified through LiDAR data, is largely correct.

“The suggestion from these data would be that were we to expand the survey of this particular region or all other regions we would find more of what we found,” Canuto said.

“It allows us to tell better stories of the ancient Maya people.”

Although LiDAR was developed in the 1960s to study clouds and atmospheric particles, its application in archaeology is relatively recent. In 2009, archaeologist couple Diane and Arlen Chase of the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, pioneered the use of LiDAR to map the Mayan city of Caracol in Belize.

In 2018, LiDAR scans revealed an ancient Mayan megalopolis hidden below the Guatemalan Jungle, allowing researchers to identify the ruins of more than 60,000 dwellings, temples, elevated highways, and other human-made infrastructure, largely hidden from sight.

The Associated Press contributed to this article.