Oxford University Press (OUP) announced that “brain rot” was elected Oxford Word of the Year for 2024, following a public vote in which more than 37,000 people participated.

In a statement released Monday, OUP defined the term as “the supposed deterioration of a person’s mental or intellectual state, especially viewed as the result of overconsumption of material (now particularly online content) considered to be trivial or unchallenging. Also: something characterized as likely to lead to such deterioration.”

According to OUP’s analysis, the use of the term increased by 230 percent between 2023 and 2024.

Oxford’s “Word of the Year”—or rather the two words being used together as one concept—is not a new term. According to OUP, “brain rot” was first used in 1854 by Henry David Thoreau, an American naturalist philosopher, in his book “Walden,” in which he detailed his life in nature and reflected on societal issues.

In his critique, Thoreau addressed his society’s preference for simplistic ideas over complex, multifaceted ones, suggesting this preference points to a broader intellectual decline.

Thoreau mused: “While England endeavors to cure the potato rot, will not anyone endeavor to cure the brain rot—which prevails so much more widely and fatally?”

Nothing since the invention of printing has been so instrumental to the dissemination of information than smartphones and the Internet, with a never-ending stream of information at our fingertips any moment of the day—or night.

The term “brain rot” initially gained traction on social media platforms, particularly on TikTok among Gen Z and Gen Alpha communities, OUP said. Its use quickly became more mainstream, given the poignancy of the label, and the very real concerns about the negative impact of overconsuming online content.

Be Good to Your Brain

Earlier this year, The Newport Institute, a U.S.-based mental health center, published advice online about how to recognize and avoid “brain rot.”

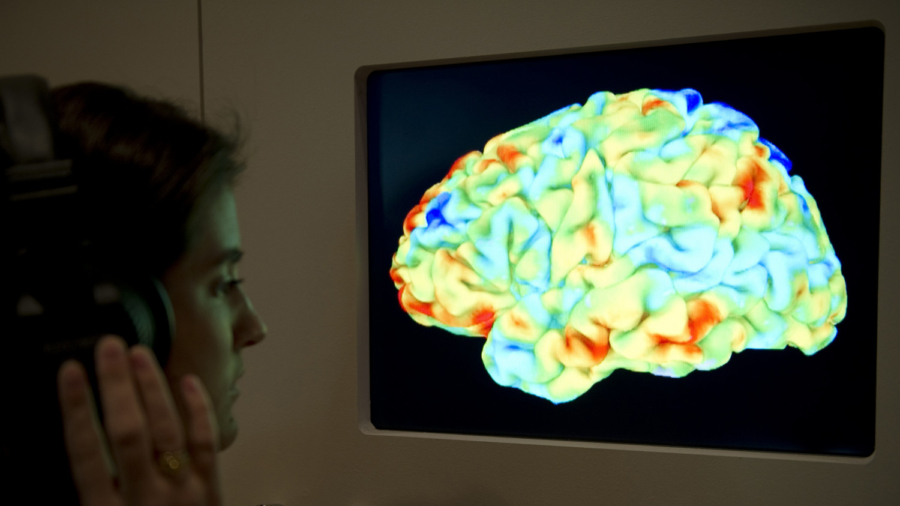

“Brain rot is a condition of mental fogginess, lethargy, reduced attention span, and cognitive decline that results from an overabundance of screen time,” the institute said, warning specifically against “doomscrolling”—the act of consuming and looking for distressing and negative news online.

But less depressing media-consumption, such as binge-watching videos on YouTube, “zombiescrolling” through endless clips on TikTok, playing video games, or combining these simultaneously with work, texting, and checking emails, can all lead to overstimulating your brain.

As a result, your exhausted brain will have difficulty planning things, organizing information, solving problems, making decisions, and recalling information.

In the long run, “brain rot” may lead to problems for our mental and physical health, The Newport Institute said.

To prevent “brain rot,” the institute recommended screen time discipline—all of us know how time whizzes by when we’re locked in on social media—and being mindful of what you consume.

“Don’t succumb to sensationalistic and negative news,” The Newport Institute cautioned, followed by advice to “diversify your media sources so you maintain a more balanced world perspective,” and to avoid content creators who feed on fear and anger.

But there are also other ways to spend your time—there is a marvelous world out there to explore, so many hobbies, skills, and trades to learn that can all give you incredible satisfaction without overloading your brain, as well as countless interesting people.

A 2020 survey by the East Carolina University showed that young adults (ages 18–25) had the lowest levels of depressive symptoms when they enjoyed more offline emotional support.

Another study from the same year, conducted by the Nottingham Trent University, showed that even just a seven-day social media abstinence significantly increased perceived mental wellbeing.

OUP’s very own Oxford Dictionary, as well as Merriam-Webster and Cambridge dictionaries have yet to include “brain rot,” although Collins already has, albeit a simpler description: “an inability to think clearly caused by excessive consumption of low-quality online content,” and “material, [especially] on the internet, that is not intellectually stimulating.”