Boeing employees raised doubts among themselves about the safety of the 737 Max. They hid problems from federal regulators and ridiculed those responsible for designing and overseeing the jetliner, according to a damning batch of emails and text messages released nearly a year after the aircraft was grounded over two catastrophic crashes.

The documents, made public Thursday by Boeing at the urging of Congress, fueled allegations the vaunted aircraft manufacturer put speed and cost savings ahead of safety in rolling out the Max. Boeing has been wracked by turmoil since the twin disasters and is still struggling to get the plane back in the air. Last month, it fired its CEO.

In the 117 pages of internal messages, Boeing employees talked about misleading regulators about problems with the company’s flight simulators, which are used to develop aircraft and then train pilots on the new equipment. In one exchange, an employee told a colleague he or she wouldn’t let family members ride on a Max. The colleague agreed.

In a message chain from May 2018, an employee wrote: “I still haven’t been forgiven by God for covering up (what) I did last year.” It was not apparent exactly what the cover-up involved. The documents contain redactions and are full of Boeing jargon. The employees’ names were removed.

Employees also groused about Boeing’s senior management, the company’s selection of low-cost suppliers, wasting money, and the Max. “This airplane is designed by clowns who, in turn, are supervised by monkeys,” one employee wrote.

In response, Boeing said that it is confident the flight simulators work properly but that the conversations raise questions about the company’s dealings with the Federal Aviation Administration in getting the machines certified.

It said it is considering disciplinary action against some employees: “These communications do not reflect the company we are and need to be, and they are completely unacceptable.”

FAA spokesman Lynn Lunsford said the simulator mentioned in the conversations had been checked three times in the past six months, and “any potential safety deficiencies identified in the documents have been addressed.”

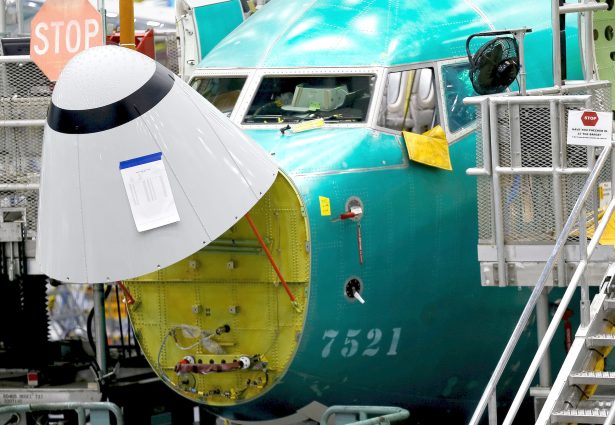

The Max has been grounded worldwide since March, after two crashes five months apart—one involving Indonesia’s Lion Air, the other an Ethiopian Airlines flight—killed 346 people. Investigators believe the crashes were caused when the jetliners’ brand-new automated flight-control system mistakenly pushed the planes’ noses down.

Boeing is still working to fix the flight-control software and other systems on the Max and persuade regulators to let it fly again. The work has taken much longer than Boeing expected, and it is unclear when the plane will return to the skies. Federal prosecutors, in the meantime, have opened a criminal investigation into the development and approval of the Max.

A lawmaker leading one of the congressional investigations into Boeing called the batch of messages “incredibly damning.”

“They paint a deeply disturbing picture of the lengths Boeing was apparently willing to go to in order to evade scrutiny from regulators, flight crews and the flying public, even as its own employees were sounding alarms internally,” said Rep. Peter DeFazio, D-Ore., chairman of the House Transportation Committee.

DeFazio said the documents detail “some of the earliest and most fundamental errors in the decisions that went into the fatally flawed aircraft.”

In one email message, an employee, believed to be a test pilot, wrote that he crashed the first few times he flew the Max in simulator testing. The email was written in May 2015, nearly two years before the FAA approved the Max for flight in March 2017.

“You get decent at it after 3-4 tries, but the first few are ugly,” the employee wrote.

In a 2015 message, a chief technical pilot said Boeing would push back hard against requirements that pilots undergo simulator training before flying the Max. One of the plane’s biggest selling points, as Boeing saw it, was that 737 pilots could easily switch to the new jet with only a small amount of computer-based training, saving airlines money.

Critics have said the FAA should have required simulator training, so pilots knew how to handle malfunctions with the new flight-control software, known as MCAS. Initially, Boeing didn’t disclose to airlines and pilots that the software was on the planes.

“I want to stress the importance of holding firm that there will not be any type of simulator training required to transition from NG (existing 737s) to MAX. Boeing will not allow that to happen. We’ll go face to face with any regulator who tries to make that a requirement,” the chief technical pilot wrote in a March 2017 message.

Another employee, in November 2014, made clear that the plane did things that pilots didn’t expect, and it was hidden from the FAA. “We don’t want to indicate to the FAA that our design conflicts with pilot expectations (esp. since the pilot responses are naive and our design has been vetted in a number of demos),” one employee wrote.

The emails add to the growing body of evidence that Boeing misled the FAA and its airline customers. In October, Boeing turned over messages in which a former senior test pilot, Mark Forkner, told a co-worker in 2016 that the MCAS was “egregious” and “running rampant” when he tested it in a flight simulator.

“So I basically lied to the regulators (unknowingly),” wrote Forkner, then Boeing’s chief technical pilot for the 737.

The grounding of the Max will cost the company billions in compensation to the families of those killed in the crashes and to airlines that canceled thousands of flights. Last month, Boeing decided to suspend production of the plane in mid-January, a decision that is rippling out through its vast network of suppliers.

CEO Dennis Muilenburg was ousted after alienating regulators, Boeing’s airline customers, and the crash victims’ families with his handling of the disaster and his overly optimistic predictions of when the plane might fly again.

Boeing’s current chairman, David Calhoun, will try to right the company when he takes over as CEO on Monday.

By David Koenig And Tom Krisher