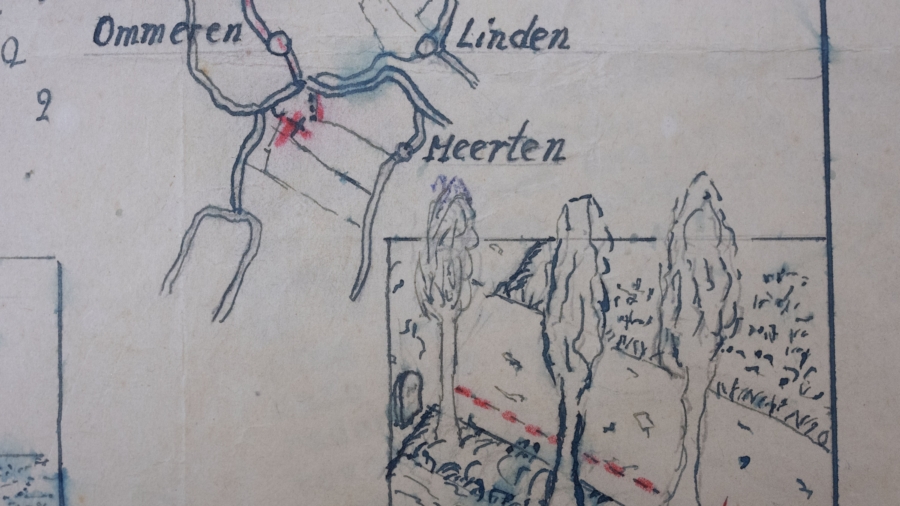

OMMEREN, Netherlands—A hand-drawn map with a red letter X purportedly showing the location of a buried stash of precious jewelry looted by Nazis from a blown-up bank vault has sparked a modern-day treasure hunt in a tiny Dutch village more than three quarters of a century later.

Wielding metal detectors, shovels and copies of the map on cellphones, prospectors have descended on Ommeren—population 715—about 80 kilometers (50 miles) southeast of Amsterdam to try to dig up a potential World War II trove based on the drawing first published on Jan. 3.

“Yes, it is of course spectacular news that has enthralled the whole village,” local resident Marco Roodveldt said. “But not only our village, also people who do not come from here.”

He said that “all kinds of people have been spontaneously digging in places where they think that treasure is buried—with a metal detector.”

It wasn’t immediately clear if authorities could claim the loot if it was found, or if a prospector could keep it.

So far, nobody has reported finding anything. The treasure hunt began this year when the Dutch National Archive published—as it does every January—thousands of documents for historians to pore over.

Most of them went largely unnoticed. But the map, which includes a sketch of a cross section of a country road and another with a red X at the base of one of three trees, was an unexpected viral hit that briefly shattered the mid-winter calm of Ommeren.

“We’re quite astonished about the story itself. But the attention it’s getting is as well,” National Archive researcher Annet Waalkens said as she carefully showed off the map.

Photos on social media in early January showed people digging holes more than a meter (three feet) deep, sometimes on private property, in the hope of unearthing a fortune.

Buren, the municipality Ommeren falls under, published a statement on its website pointing out that a ban on metal detection is in place for the municipality and warned that the area was a World War II front line.

“Searching there is dangerous because of possible unexploded bombs, land mines and shells,” the municipality said in a statement. “We advise against going to look for the Nazi treasure.”

The latest treasure hunters aren’t the first to leave the village empty handed.

The story starts, Waalkens said, in the summer of 1944 in the Nazi-occupied city of Arnhem—made famous by the star-studded movie “A Bridge Too Far”—when a bomb hit a bank, pierced its vault and scattered its contents—including gold jewelry and cash—across the street.

German soldiers stationed nearby “pocket what they can get and they keep it in ammunition boxes,” Waalkens said. As World War II nears its end in 1945, the Netherlands’ German occupiers were pushed back by Allied advances. The soldiers who had been in Arnhem found themselves in Ommeren and decided to bury the loot.

“Four ammunition boxes and then just some jewelry that was kept in handkerchiefs or even cash money folded in. And they buried it right there,” she said, citing an account by a German soldier who was interviewed after the war by Dutch military authorities in Berlin and who was responsible for the map. The archive doesn’t know if the soldier is still alive and hasn’t released his name, citing European Union privacy regulations.

Dutch authorities using the map and the soldier’s account went hunting for the loot in 1947. The first time, the ground was frozen solid and they made no headway. When they went back after the thaw, they found nothing, Waalkens said.

After the unsuccessful attempts, the German soldier said “he believed that someone else has already excavated the treasure,” she added.

That detail was largely overlooked by treasure hunters who descended on Ommeren in the days after the map’s publication. On a recent visit to the village, there were no diggers to be seen as peace and quiet has returned to Ommeren.

But the village’s brief brush with fame left a sour taste for some residents. Ria van Tuil van Neerbos said she didn’t believe in the treasure story, but understood why some did.

“If they hear something, they’ll head toward it,” she said. “But I don’t think it’s good that they just dug into the ground and things like that.”

By Aleksandar Furtula