A student from the University of California Irvine (UCI) may have accidentally invented a battery that could last for a lifetime, UCI reported.

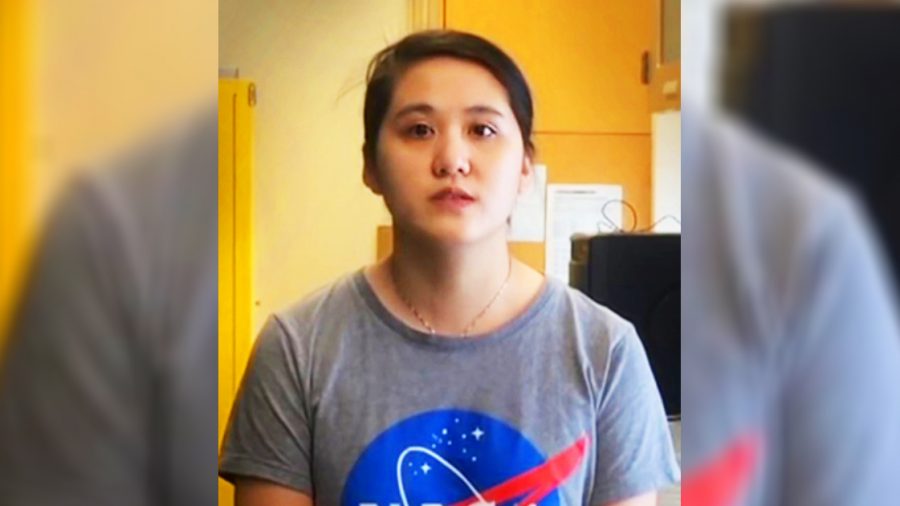

Dr. Penner Research Group team member and University of California, Irvine Doctoral candidate Mya Le Thai discovered a…

Posted by UCI Applied Innovation at the Cove on Monday, July 11, 2016

Mya Le Thai was doing research on making nanowire rechargeable batteries in 2016.

Since then, Thai graduated with a Ph.D. and works as Senior Process Engineer at Intel Corporation.

Thai seems to have possibly stumbled on a way to make a battery that could, in theory, last 400 years, Business Insider reported.

ICYMI: Better batteries through chemistry UCI breakthrough may extend the life of computers, smartphones and…

Posted by University of California, Irvine on Monday, May 16, 2016

The standard lithium-ion battery can last up to a few years with 300 to 500 recharge cycles. While studying gold nanowire batteries, she found that commercial gold nanowire batteries could last up to 5,000 to 6,000 recharge cycles.

This is possible because nanowire is thinner than a strand of hair and can store and transfer greater amounts of electricity. It is also dependent on whether the nanowire is made of material that can conduct electricity.

Thai stumbled on what she called a “crazy” discovery when she coated some gold nanowire in an electrolyte gel that then withstood 200,000 recharge cycles during three months of testing, Business Insider reported.

An iPhone typically has 500 recharge cycles before its total capacity drops to 80 percent of its original capacity.

The performance in her testing was consistent and the nanowires didn’t fracture after repeated use, UCI reported.

She said she was only “playing around” when she made the discovery.

This newfound battery could be applied to cars, houses, planes, construction tools, space exploration, and other electrical appliances and devices.

Although this discovery is quite a game-changer, the researchers are still trying to figure out why the gel allowed the battery to increase or sustain its recharge cycle.

They are also looking for ways to reduce the cost of producing the battery by finding an alternative to gold.

(Video courtesy of Maryland Nanocenter)

European Power Firms Aim to Harness Electric Car Batteries

E.ON and EDF are already working with Nissan to develop services that allow power stored in electric vehicle batteries to be sold back to the grid—and now they’re trying to persuade European carmakers to follow suit.

With millions of electric cars expected on European roads over the next decade, utility firms see both an opportunity to sell drivers more electricity and a risk that surges in charging at peak times could destabilize stressed power grids.

That’s why E.ON is working with Nissan to develop so-called vehicle-to-grid (V2G) services, including software for aggregating and marketing charging data so the German power company can predict peaks and troughs in electricity demand.

Nissan’s idea is that if you charge your electric vehicle (EV) at off-peak times and are prepared to sell power back to the grid when it’s under strain, you could effectively charge for free.

The idea of using millions of EV batteries as large virtual power plants to put power back into the grid has been around for years though the concept is still mostly at the pilot phase, mainly because there are very few EVs on the roads now.

But its appeal to the power industry is obvious.

With a typical car driving less than 10 percent of the day, the rest of the time car batteries could be used to balance out demand and supply swings in energy networks that increasingly need to juggle intermittent solar and wind power.

That’s the case in Germany in particular as it is phasing out baseload nuclear and coal-fired plants, unlike France and Japan which are sticking with nuclear to ensure a secure supply.

Epoch Times reporter Michael Wing contributed to this article.