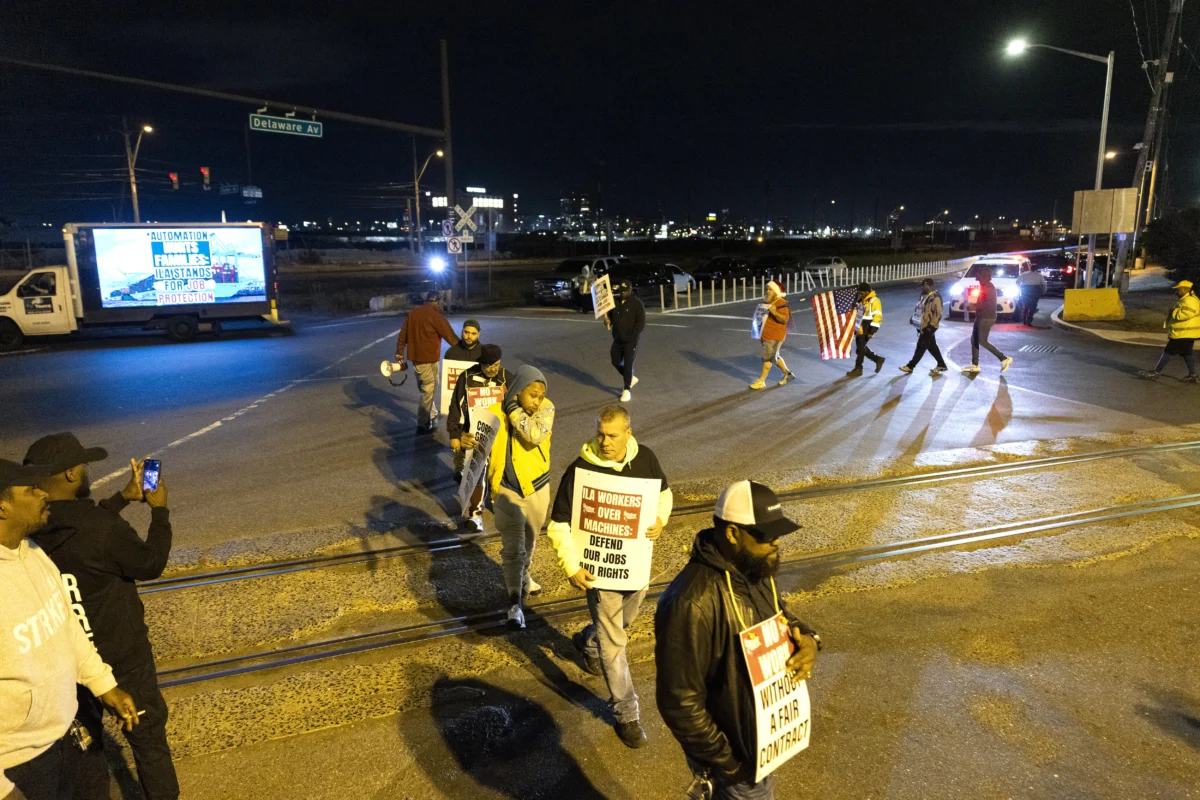

Dockworkers at ports from Maine to Texas began walking picket lines early Tuesday morning in a strike over wages and automation that could reignite inflation and cause shortages of goods if it goes on more than a few weeks.

The contract between the ports and about 45,000 members of the International Longshoremen’s Association expired at midnight, and even though progress was reported in talks on Monday, the workers went on strike. The strike affecting 36 ports is the first by the union since 1977.

According to a JP Morgan analysis, the strike could cost the U.S. economy as much as $5 billion daily. Peter Earle, senior economist at the American Institute for Economic Research, said that some of those impacts are already being felt with shipping containers doubling in price.

“They’re usually about $2,500 to rent. They’ve already run up to about $6,000, which tells me the lot of shipping firms are already buying these things. They’re trying to reserve them just in case they have problems,” he told NTD on Monday.

He said he expects such price hikes would likely already have trickled into the economy, and if the strike proceeds, Americans would likely immediately feel the impact in the “most commodity goods” such as fuel and food.

The strike, which began at 12:01 a.m. on Tuesday, could impact ports that handle 75 percent of the nation’s annual supply of bananas, which is approximately 3.8 million metric tons, according to the American Farm Bureau Federation.

Maritime expert Rockford Weitz told NTD that the strike could disrupt the holiday shopping season and impact the imports of goods such as fruits, vegetables, coffee, clothing, furniture, pharmaceutical goods, and even European cars.

“This will have consequences on the shelves of Costco, Costco wholesale, Target, Home Depot, etc., etc., etc., Walmart,” said Weitz, a maritime studies professor at Tufts University.

The National Retail Federation (NRF) said in a Sept. 11 press release on the issue that even a one-day shutdown could cost at least $1 billion, referencing economists’ estimates for the 2002 West Coast port lockout that lasted 11 days, which they said could be even worse in today’s economy.

According to Grace Zwemmer, associate U.S. economist at Oxford Economics, trade flow disruptions from the strike could reduce GDP growth by up to $7.5 billion per week, ranging from 0.08 to 0.13 percent.

She said inflation likely won’t be affected but delays in products are likely, along with higher consumer and producer prices.

“The good news is that the risk to inflation is limited, as freight rates have steadily dropped since August and ongoing deflation in China has put downward pressure on import prices,” Zwemmer said in a research note.

In the same press release, the NRF said if the strike poses a potential threat to the U.S. economy, President Joe Biden could invoke the Taft-Hartley Act, which forces an 80-day “cooling off period” to open the ports and force negotiations between the two parties. Former President George W. Bush invoked the act to end the 2002 lockout.

But Biden has signaled he doesn’t plan to do that. “Because it’s collective bargaining, I don’t believe in Taft-Hartley,” he told reporters on Sunday.

Earle, in an interview before the strike began, said that with high prices and inflation impacting the economy, he would expect Biden to invoke his right.

“I expect that if we don’t see a deal by midnight, the Biden administration is going to employ their rights under the Taft Harley Act … if this strike occurs. And the longer it goes on, the more they have to lose in terms of economic performance,” he said.

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce has also called on the Biden administration to invoke Act in a recent letter.

The USMX, representing 36 ports from Maine to Texas, responded to the striking workers with an offer of nearly 50 percent in wage increase over a six-year contract, according to a statement from the alliance. The offer includes tripling employer contributions to retirement plans and strengthening healthcare options while maintaining current language to limit automation.

“We are hopeful that this could allow us to fully resume collective bargaining around the other outstanding issues in an effort to reach an agreement,” the alliance statement said.

According to their statement, the alliance has also offered to renew the union’s contract, which is set to expire on Sept. 30.

In contrast, the ILA, representing 45,000 dockworkers, is demanding a 77 percent pay raise over six years to address inflation concerns. The union argues that while many of its members can earn over $200,000 annually, it requires substantial overtime work to reach anywhere near that figure.

The current top pay rate for longshoremen is $44.25 per hour, translating to about $92,000 annually for a standard 40-hour work week, according to U.S. pay software and data company payscale.com.

According to international shipping company Universal Cargo, ILA workers’ current top pay is around $39 per hour and if their demands are met, that could jump to $69 per hour after six years, reflecting an increase of 77 percent.

The dispute extends beyond wages. The ILA, which hasn’t held a strike since 1977, is also demanding a complete ban on automated cranes, gates, and container-moving trucks in port operations. This stance on automation has become a major point of contention in the negotiations, which haven’t formally been held since June.

These ports, stretching from Maine to Texas, play a crucial role in the nation’s supply chain. Experts say a prolonged strike could have ripple effects that would be felt into next year.

“If the strikes go ahead, they will cause enormous delays across the supply chain, a ripple effect which will no doubt roll into 2025 and cause chaos across the industry,” said Jay Dhokia, founder of supply chain management and logistics firm Pro3PL, in an interview on Monday.

He said concerns regarding the strikes have already diverted some shipments to the West, where dockworkers belong to a different union, adding to route congestion. The strike would also likely be felt internationally with U.S. trading partners like the United Kingdom, he said.

The USMX has requested an extension of the current contract to allow for further negotiations, according to their statement.

Port of Long Beach CEO Mario Cordero has issued a statement on the contract negotiations, saying the port is hopeful an agreement will be reached but is prepared if not.

“We continue to be in close contact with our ocean carriers, terminal operators, railroads, equipment providers, and labor and industry partners to monitor the situation and to do our part to keep the national supply chain operational,” he said.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.