News Analysis

NEW YORK—As lawyers in the criminal trial of former President Donald Trump prepare to deliver their summations on Tuesday, and the jury makes ready to begin deliberating as soon as the middle of the week, speculation runs high as to whether proceedings will end in an acquittal, a guilty verdict, or a hung jury.

If President Trump is convicted, evidentiary concerns and Justice Juan Merchan’s conduct are likely to raise substantive issues for the defense to pursue at the appellate level, according to one legal expert. But other judicial experts disagree, saying it is premature to try to assess the trial’s fairness.

Throughout the trial, Justice Merchan has consistently sustained prosecutors’ objections to defense lawyers’ questions, and has made concessions to the government while denying a bulk of defense motions, said Marc Clauson, a professor of law and constitutional theory at Cedarville University in Ohio who has studied the proceedings closely from their beginning.

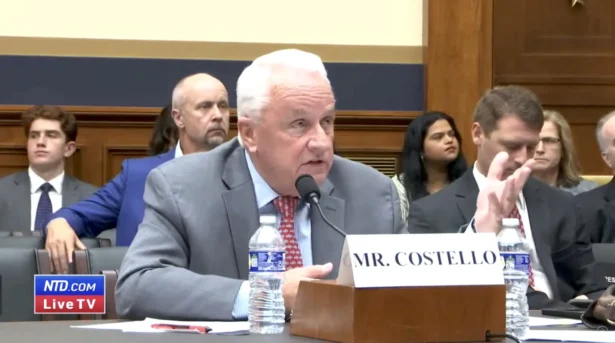

In addition, the judge’s words and actions during a highly tense moment in the courtroom this week—as defense witness Robert Costello, a former federal prosecutor, testified—renders the judge vulnerable to the very charges of unseemliness he leveled at Mr. Costello, Mr. Clauson believes. Moreover, the failure of the government to set forth a clear legal case for its indictment of President Trump will raise due process issues at the appellate level, he added.

“I’ve been following all the ins and outs and nuances of the trial,” Mr. Clauson told The Epoch Times. “District Attorney Alvin Bragg made very public statements about his desire to ‘get’ Trump, so it certainly looks political. Furthermore, there are a lot of things that the judge has done wrong and that can be raised on appeal.”

Courtroom Drama

On May 20, a blow-up that occurred when the defense put Mr. Costello on the stand made headlines.

Just minutes into Mr. Costello’s testimony, prosecutor Susan Hoffinger repeatedly interrupted Trump lawyer Emil Bove’s direct examination with objections as to the relevance or the leading nature of the defense counsel’s questions about relations between Mr. Costello and former Trump associate and lawyer Michael Cohen.

Mr. Costello grew so frustrated with the interruptions that he exclaimed “jeez!”

This led the judge to call a sidebar and then furiously address the witness.

“Mr. Costello, I’d like to discuss proper decorum in my courtroom, okay? So as a witness on the stand, if you don’t like my ruling, you don’t say ‘jeez.’ And if a question is overruled, you don’t say ‘strike it,’ because I’m the only one who can strike an answer. And if you don’t like my ruling, you don’t look at me side-eyed, and you don’t roll your eyes. Do you understand that?”

The judge then seemed to gain the impression that Mr. Costello was not merely looking at him, but staring with clear intent to intimidate.

“Are you staring me down? Clear the courtroom!” the judge shouted.

After clearing the courtroom, the judge had angry words with the defense counsel, threatening to hold Mr. Costello in contempt and to strike his entire testimony.

Though cited in many reports as an example of Mr. Costello’s impudence, Mr. Clauson contends that the incident actually reflects Judge Merchan’s bias.

“Justice Merchan continually allowed the prosecution to interrupt Mr. Costello when he was trying to make his points about his relationship with Michael Cohen, and the judge should not have been sustaining all those objections, those were very relevant statements,” Mr. Clauson said.

“Also, the judge should not have allowed himself to become really personal about these things. That’s not becoming a judge,” he added.

Rulings

Mr. Clauson sees the proceedings as littered with examples of the judge’s stance that favored the prosecution. In the course of the trial, and especially over the past week, Justice Merchan has issued a series of rulings in favor of the prosecution and disadvantageous to the defense, he said.

On May 21, Mr. Bove made a case for eliciting testimony from former Federal Election Commission chairman Bradley Smith in order to help the jury understand the ins and outs of election law and what the Federal Election Campaign Act—which the government claims President Trump violated—does and does not cover.

Mr. Bove tried to explain why, without Mr. Smith’s elucidation of the finer points of law, the jury might mistakenly convict President Trump on the basis of a misunderstanding.

One of the charged offenses—a falsification of business records—does not itself constitute evidence that the defendant committed that falsification with conscious intent, or mens rea, to carry out a separate felony, the defense noted.

Even if the government can provide evidence of fraudulent bookkeeping, this falls short of the standards established under New York business law statute 175.10, Mr. Bove said. The defense has repeatedly argued that all candidates for office naturally want to influence the course of an election, and the government has a high bar to meet here if it seeks to prove that one criminal offense aided and compounded the commission of a separate one.

“What they’re talking about is a civil conspiracy which can’t serve as a predicate on the business law charges. The U.S. Supreme Court has held time and time again that for there to be a criminal conspiracy, there has to be a criminal object,” he said.

“The problem, judge, is that the mens rea for the conspiracy charge has to match the highest mens rea for the object. … Otherwise, you just have a civil conspiracy that can’t be used to convict Mr. Trump,” Mr. Bove pressed.

A Battle of the Experts

Justice Merchan, however, maintained that the defense wanted Mr. Smith to take the stand not to answer questions about facts important to the case, but to offer general legal opinions.

“If Mr. Smith were to testify on these subjects, the people would have to be given the opportunity to elicit testimony from an expert. This would result in a battle of the experts, which would only serve to confuse and not enlighten the jury,” the judge said.

Mr. Bove tried to sway Justice Merchan, arguing that clarifying language in the judge’s instructions to the jury—such as “for the purpose of influencing an election,” was, as Mr. Bove put it, “absolutely critical” to helping the jury understand the evidentiary burden that the government must meet.

“It’s not the best position for a lawyer to be asking questions in court, we understand that. But I’m wondering if you’re willing to give us any sense on whether you’re going to instruct the jury on these issues,” Mr. Bove pled.

To the frustration of the defense, the judge shot down this request, on grounds of both its timeliness and a more philosophical stance on the judge’s part. Mr. Bove could have raised these issues sooner but was doing so just the government wound up its case, Justice Merchan said.

“I offered guidance and you’ve known for months that this is not new, you’ve known for months what my position would be. If you had concerns about these specific rulings, you could have come to me some time ago, and now you’ve waited until the people are almost done,” the judge stated.

“I can tell you that when it comes to these types of matters, I often think that less is better. You must remember the people are not required to prove these [charges] beyond a reasonable doubt, and that reduces the burden on every word, every phrase,” he continued.

The Question of Objectivity

Mark Graber, a professor at Francis King Carey School of Law in Maryland, is among those who believes that President Trump has gotten a fair trial. Judges do not have carte blanche to rule in accordance with their personal political views, and Justice Merchan is no exception, he said.

“Most trial judges, Democrats or Republicans, are fair. If they are not, they get overruled and they know it,” Mr. Graber said.

David Schultz, a professor in the departments of legal studies and political science at Hamline University in St. Paul, said it is premature to weigh in on the fairness of the proceedings.

“The question when it comes to a fair trial is not whether New York City is deeply blue or Democratic; it is whether the parties will be able to empanel a jury of 12 individuals who could keep an open mind about the case and render a verdict based on the facts and law. Unless one can find some jury tampering, undisclosed jury biases, or procedural errors in the case, we must presume a fair trial,” Mr. Schultz told The Epoch Times.

“If one concludes now that a fair trial was not possible, what do we say if he is acquitted?”

Mr. Bragg’s office did not immediately reply to a request for comment.

From The Epoch Times