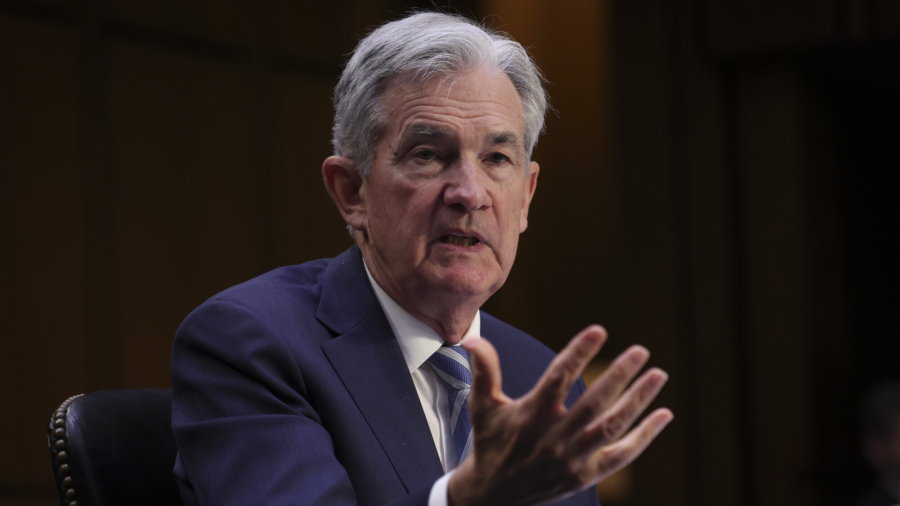

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell said he thinks it’s rather “likely” that the forces of de-globalization will mount, leading to a more fractionalized new normal characterized by higher inflationary pressures, lower productivity, and slower economic growth.

Powell made the remarks on June 29, during a panel discussion at the European Central Bank’s annual policy forum in Sintra, Portugal.

“We’ve lived through a period of disinflationary forces around the world—this is globalization, aging demographics, low productivity, technology enabling all of that,” Powell said, describing it as a world where inflation was generally “not a problem” in most advanced economies.

“Since the pandemic, we’ve been living in a world where the economy is being driven by very different forces, we know that,” he continued, noting that what remains unknown is whether things will go back to a prior disinflationary environment and, if so, to what extent.

“We suspect that it will be kind of a blend,” the Fed chief said.

“In the meantime, we’ve had a series of supply shocks, we’ve had very high inflation across the world, certainly through all the advanced economies, and … we’re learning to deal with it,” he said, with his remarks coming as central banks around the world have, in general, been caught flat-footed by persistently high inflation and have rushed to tighten loose monetary settings to bring down soaring prices.

‘Certainly a Possible Outcome’

Powell said the Fed’s job of achieving price stability and maximum employment in this new normal with new forces at work has been a “very different exercise” than the U.S. central bank has undertaken over the past 25 years while suggesting that slower economic growth would be an inevitable tradeoff in fighting inflation.

“If what we see, for example, is a re-division of the world into competing geopolitical and economic camps, in a reversal of globalization, that certainly sounds like lower productivity and lower growth,” he said.

“That’s certainly a possible outcome and I think probably, to some extent, a likely outcome,” Powell said.

Asked by the panel moderator to comment on whether the U.S. economy can withstand an “onslaught” of interest rate hikes, Powell replied by saying that America’s economy is in “pretty strong shape,” noting factors like high household savings and a tight labor market.

He added that the aim of the Fed’s rate-hiking cycle is to have economic growth “moderate,” calling it a “necessary adjustment” that aims to bring down demand in the U.S. economy and bring it more into alignment with supply.

“Right now, supply and demand are really out of balance in many parts of the U.S. economy, the labor market being a big example of that,” he said, with the unemployment rate currently at 3.6 percent and around two job vacancies for every job-seeker.

“We need to get them better in balance so inflation can come down,” he added, suggesting the Fed is prepared to tolerate some labor market pain as the price of cooling inflation.

‘No Guarantee’ of a Soft Landing

Powell said that he sees “pathways” for the Fed to achieve a so-called soft landing, where inflation drops but unemployment doesn’t move up significantly, though he added that “there’s no guarantee that we can do that.”

“We believe we can do that,” Powell said, but “it’s obviously something that’s going to be quite challenging.”

Powell’s remarks come on the heels of recent statements made by other Fed officials indicating that the central bank believes its current aggressive monetary tightening cycle is necessary to quell inflation and will lead to a slowdown in economic growth—but that a recession is not inevitable.

Cleveland Fed President Loretta Mester, a voting member of the interest rate-setting Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), said in a Wednesday interview on CNBC that the Fed is “just at the beginning” of its rate-hiking endeavor and that it carries the risk of a recession.

‘Bumpy Ride’

Regardless of the possibility of an economic contraction, Mester insisted that the Fed needs to keep hiking rates “expeditiously” and that, in order to get a handle on inflation, she said the central bank might have to err on the side of tighter financial conditions.

“We’re on a path now to bring our interest rates up to a more normal level and then probably a little bit higher into restrictive territory,” she told CNBC.

What Mester described as a “bumpy ride” toward tighter financial conditions would likely drive up the unemployment rate from the current 3.6 percent to between 4 percent and 4.25 percent over the next two years, she predicted.

New York Fed President John Williams said in a separate interview on CNBC that he, too, sees a recessionary risk, though that is not his “base case.”

Williams predicted the U.S. economy would slow its pace of growth for the entire year to between 1 percent and 1.5 percent, calling it a “slowdown that we need to see in the economy to really reduce the inflationary pressures that we have and bring inflation down.”

The Fed hiked rates by 75 basis points at its last meeting, with Fed Funds futures contracts putting the odds of another 75 basis point hike at the next July policy meeting at 89.1 percent. That would bring the benchmark overnight deposit rate up to a target range of between 2.25 percent and 2.50 percent from the current 1.50 percent to 1.75 percent.

Mester said that the Fed would likely have to keep hiking rates to a terminal rate of between 3 percent and 3.5 percent.

Fed Dovish Pivot?

Nick Reece, VP of Macro Research and Investment Strategy at Merk Investments, told The Epoch Times in an emailed statement that market expectations for Fed rate hikes have shifted.

“The expected Fed rate hiking cycle peak has shifted higher and sooner over the past month: from an expected peak in mid-2023 at about 3.25 percent to the end of 2022 at 3.75 percent,” he said.

Reece added, however, that history shows that Fed hiking cycles don’t typically last as long or go as high as markets expect, and that, “in fact, the Fed dovish pivot may have already started.”

He pointed to the fact that 2-year Treasury yields spiked to 3.45 percent several weeks ago and have since fallen back to around 3 percent.

“The 2-year yield typically peaks at or before Fed rate hiking cycle peaks and above rate hiking cycle peaks,” he said, with his remarks coming as market watchers try to predict when the Fed might pivot away from tighter policy and adjust portfolio allocations to profit from the phase shift.

From The Epoch Times