New Jersey’s largest city plans to test a socialist-style income program that has already failed abroad.

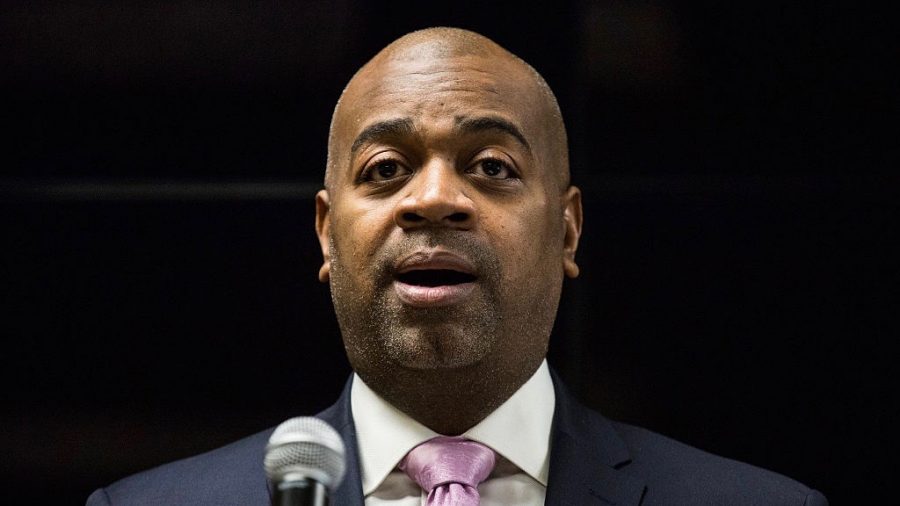

Newark Mayor Ras Baraka said he would test universal basic income, a program of guaranteed income for residents that’s typically given whether or not people have a job, and with no discretion on how the money is used once it’s in the recipients’ hands.

“We believe in Universal Basic Income, especially in a time where studies have shown that families that have a crisis of just $400 a month may experience a setback that may be difficult, even impossible to recover from,” said Baraka, according to Fox News.

Baraka announced his intentions for the program at his State of the City address. He did not say what portion of residents would take part in the test program nor how it would be funded, according to National Review. He only said the city will develop the pilot program with the help of a task force.

In 2017 Finland tested a similar program of guaranteed income, giving $635 a month to 2,000 unemployed residents. Finland shuttered the program by 2019.

The program was designed to see if people getting income with no attached obligations would be likely to find work, MIT Technology Review reported. A preliminary look at the results found that the participants were no more likely to look for jobs than another test group that was not given any money.

“Universal basic income is essentially a form of socialism, and there is a reason why socialism has always failed,” said Jenna Ellis, director of public policy for the James Dobson Family Institute, via Fox News. “When you’re taxing people and redistributing wealth without merit, that encourages laziness. And that’s what we saw in Finland.”

Capri Cafaro, a former member of the Ohio state senate, said the program was both too expensive and the wrong solution for poverty.

“In the case of Finland, it was as much money as the entire government budget to be able to provide a universal basic income,” Cafaro told Fox News. “It would be better off to invest strategically in things like workforce development to deal with the skills gap to help reduce unemployment.”

Failed in Finland. Failed in Ontario.

Ras Baraka doesn’t care. He’s politicking with the suburbs’ money. https://t.co/qRXrdLuioY

— Matt Rooney (@MattRooneyNJ) March 18, 2019

Ontario, Canada ended a similar program in 2018, finding it “not sustainable” and “expensive” for the government.

Ontario sought to find out if people in low-paying jobs would benefit if a universal income were to replace welfare. The pilot program included 4,000 participants across three regions of the province.

Lisa MacLeod, who administers social services for Ontario, said the program was “clearly not the answer for Ontario families.”

“It was certainly not going to be sustainable,” MacLeod said, via The Guardian. “Spending more money on a broken program wasn’t going to help anyone.”

The Canadian program gave $13,000 per year to single people who made less than $26,000, and $19,000 to couples who made less than $37,000.

“I just don’t think it’s affordable,” Ontario labor lawyer David Wakely told the Associated Press, before the experiment ended. “The numbers are just completely unmanageable. The expense of this thing is huge. It is monumental.”

Meanwhile, the concept of universal basic income remains popular among liberal political circles in the United States, National Review reported.

Stockton, California started a universal basic income program last month, although the program includes only 130 participants. They receive $500 per month in the form of debit cards.

Chicago mayor Rahm Emmanuel set up a task force last year to study feasibility for a universal basic income program. Pending legislation is aimed at running a test program on 1,000 Chicago families.

Upstart presidential candidate Andrew Yang wants such a program on a national scale. He said he wants every American to get $12,000 annually.

Cafaro thinks that in a developed country like the United States, such programs would be counterproductive.

“Let’s give people tools to help them get in the workforce, not to sit around,” Cafaro told Fox.