TOKYO—Japan declared the name of its new imperial era when Crown Prince Naruhito becomes emperor on May 1, with Prime Minister Shinzo Abe saying it emphasized traditional values at a turning point in the nation’s history.

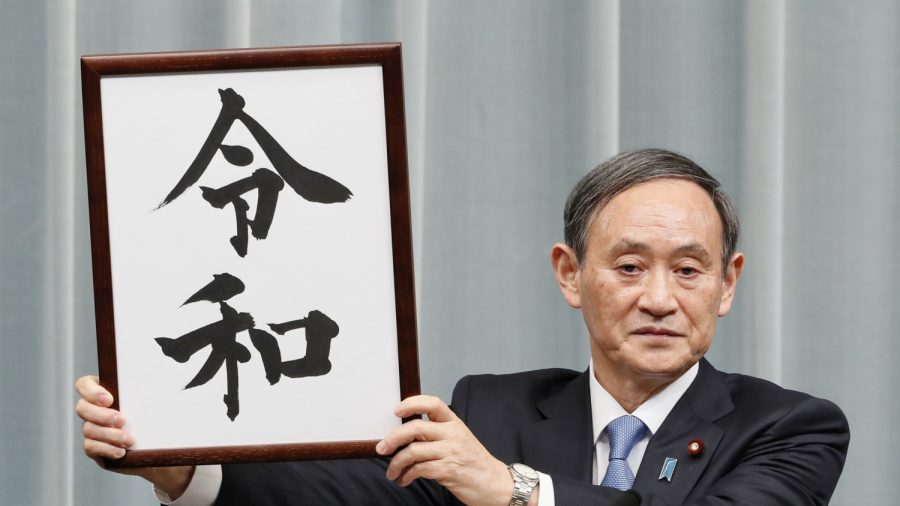

Crowds watching giant television screens across Tokyo roared and raised their phones to take photos as a somber Chief Cabinet Secretary Yoshihide Suga held up a white placard with the new name—Reiwa—written in two characters in black ink.

The country had been anxiously awaiting the new era name, or “gengo,” which is used on coins, calendars, newspapers and in official paperwork, and over time captures a national mood.

The first character means “good” and “beautiful” as well as “order” or “command”, while the second means “peace” or “harmony”.

The new name emphasized the beauty of Japan’s traditional culture and a future in which everyone would be able to achieve their dreams, especially young people, Abe said.

“Our nation is facing a big turning point, but there are lots of Japanese values that should not fade away,” he told a news conference, adding the name “signals that our nation’s culture is born and nourished by people’s hearts being drawn beautifully together.”

Naruhito’s ascension to the Chrysanthemum Throne will come a day after his father, Emperor Akihito, abdicates on April 30, ending the Heisei era, which began in 1989. He will be the first emperor to abdicate in Japan in over two centuries.

The announcement came a month early so government offices and companies can update computer software and make preparations to avoid glitches when the new era begins next month.

Japanese Poem

Public response to the new name was largely positive on Twitter and Facebook, and people on the streets of Tokyo generally voiced approval.

“It’s a gentle, peaceful name,” said Masaharu Hannuki, a 63-year-old man outside Shimbashi train station where free special edition newspapers were handed out. “We want this to be an era where children can shine in a calm future.”

The new name was taken for the first time from an ancient anthology of Japanese poems, the Manyoshu, instead of previous names from old Chinese texts. Experts said it reflected Abe’s conservative political agenda that emphasizes national pride.

“It is a collection which expresses our nation’s rich culture, which we should take pride in, along with our nation’s beautiful nature,” Abe said. “We believe this national character should be passed along to the next era.”

Makoto Ueno, a Manyoshu expert and professor at Nara University, said the name marked a significant change.

“It means the gengo has entered a new chapter,” he said. “The system which originated with the Chinese emperor system has been made alive in Japan.”

“Reiwa” Rally

The broader stock market shrugged off the announcement, but several shares rose due to their connection with the name.

Shares in advertising firm Ray Corp, which sounds like the first syllable of the new name, soared 7.9 percent.

Umenohana Co, a restaurant chain known for its tofu dishes, was up as much as 2 percent as the company name appears in a section of the Manyoshu from which Reiwa was taken.

Guidelines stipulated that the era name should be appropriate to the ideals of the nation, consist of two “kanji,” or Chinese characters, and be easy to write and read. It cannot be in common use or have been used in a previous combination.

While use of the Western calendar has become widespread in Japan, many Japanese count years by gengo or use the two systems interchangeably.

Scholars and bureaucrats had drawn up a list of candidates, and the cabinet made the final decision after consulting an advisory panel.

There have been four era names in Japan’s modern history: Meiji (1868-1912), Taisho (1912-1926), Showa (1926-1989) and the current Heisei, meaning “achieving peace”.

City offices and government agencies have been preparing for the new era name for months, aided by computer systems firms such as Fujitsu Ltd and NEC Corp.

Many computer programs have been designed to make it easy to change the gengo.

Over time, it comes to symbolize the national mood of a period, similar to how “the ’60s” evokes certain images, or how historians refer to Britain’s “Victorian” or “Edwardian” eras, tying the politics and culture of a period to a monarch.

The three decades of the Heisei era saw the collapse of Japan’s frothy “bubble” economy, years of economic stagnation, a series of natural disasters and the spread of social media.

By Elaine Lies and Linda Sieg