NASA announced on Sept. 27 it has spotted a unique tidal disruption event whereby a black hole devoured a sun-sized-star in a galaxy hundreds of millions of light years away.

Such an event whereby the galactic center—a black hole, most often—exerts so much gravity on a celestial body that it actually rips it apart (a phenomenon, also known as spaghettification) happens an average only once in every ten thousand years or more in any given galaxy, according to a report published in The Astrophysical Journal.

This particular event happened some 375 million years ago in the constellation Volans. It created a flare of electromagnetic radiation that was detectable by NASA’s telescopes. The entire event was completed in a little over two months, the scientists reported to the journal.

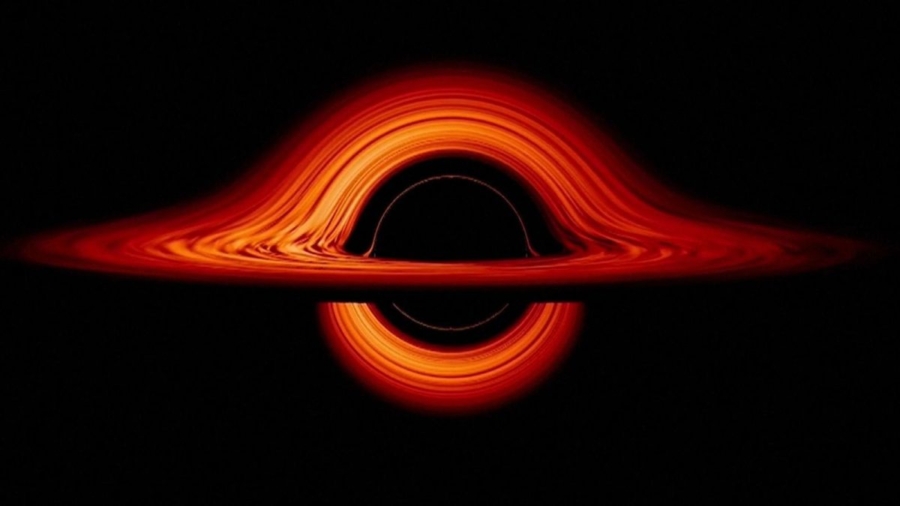

Researchers used a worldwide network of 20 robotic telescopes called ASAS-SN (All-Sky Automated Survey for Supernovae) to detect the phenomenon and then turned to TESS, or the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite—NASA’s exoplanets research telescope—to record the whole event from beginning to end. It then released an animated video of the cosmic showdown.

Patrick Vallely, a co-author of the study and National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellow at Ohio State, said, “We were very lucky with this event in that the patch of the sky where TESS is continuously observing is small, and in that this happened to be one of the brightest tidal disruption events we’ve seen.”

He added, “Due to the quick discovery and the incredible TESS data, we were able to see this event much earlier than we’ve seen others.”

Leader of the research project and astronomer for the Carnegie Institution for Science in Pasadena, California, Thomas Holoien, said: “This was really a combination of both being good and being lucky, and sometimes that’s what you need to push the science forward.

“TESS data let us see exactly when this destructive event, named ASASSN-19bt, started to get brighter, which we’ve never been able to do before,” Holoien said in a statement on the NASA website. “The early data will be incredibly helpful for modeling the physics of these outbursts,” he added.

This has been about the 40th occasion known in history of this type of disruptive event, but never before have scientists been able to witness the event so vividly.