A new gravity study on Mars has revealed dense structures beneath its largest volcano that suggest there could be volcanic activity, according to research presented at the Europlanet Science Congress 2024 in Berlin, Germany.

Assistant Professor Bart Root of Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands led the study, which combined data and models from multiple missions to look at variations in Mars’ gravity field that was used to detect the structures.

Joined by colleagues from Utrecht University, the researchers studied tiny deviations in the orbits of satellites to examine Mars’ gravity field, which they said could reveal clues of mass distribution beneath the surface of the red planet.

What researchers found in the planet’s northern polar plains were mysterious dense structures of varying sizes, hidden beneath smooth sediment layers, on what is believed to be an ancient seabed.

“These dense structures could be volcanic in origin or could be compacted material due to ancient impacts,” Root said in a Sept. 13 news release.

First established in 2006, the Europlanet Science Congress is the largest planetary science meeting in Europe covering an “extensive range” of planetary sciences regularly attracting about 1,200 participants, according to the recent announcement.

According to the study, researchers found about 20 mysterious dense structures hidden beneath the sediment, which appear invisible on the surface but are 300 to 400 kg/m3 denser than their surroundings.

“There seems to be no trace of them at the surface. However, through gravity data, we have a tantalizing glimpse into the older history of the northern hemisphere of Mars,” Root said.

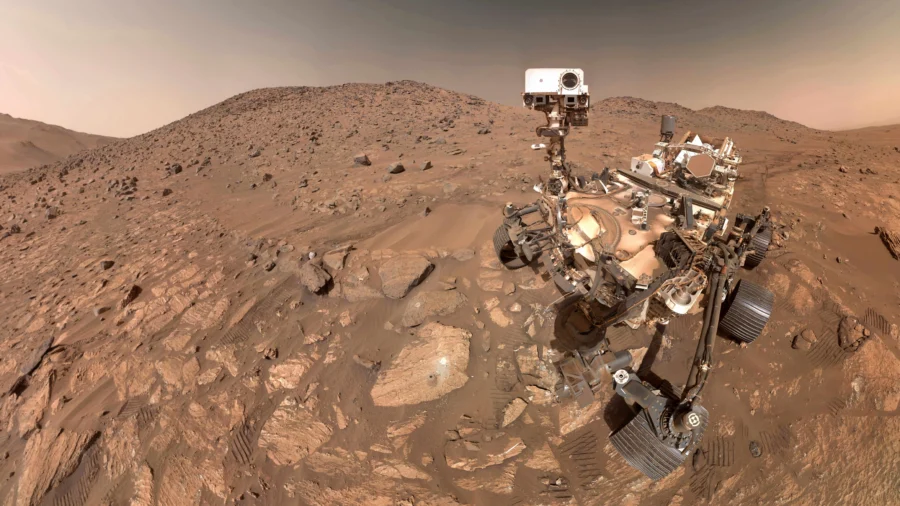

Data showed new information about Mars’ Tharsis volcanic region, which is home to the largest known volcano in the solar system, known as Olympus Mons. The gravity field in the Tharsis area exhibits unexpectedly weak gravity, despite the density of volcanoes, which could mean there could be volcanic activity down below.

“It shows that Mars might still have active movements happening inside it, affecting and possibly making new volcanic features on the surface,” Root said.

The anomaly, called light gravity, is occurring in an area about 1,750 kilometers across and 1,100 kilometers deep, which researchers said is giving the Tharsis region a boost upward, and could be from lava moving down below.

“This could be explained by [a] huge plume of lava, deep within the martian interior, traveling up towards the surface,” researchers wrote.

The study also used data from NASA’s InSight mission, which gave researchers “vital information” about Mars’ hard outer layer, according to Root.

He said the new findings will make scientists rethink their understanding of Olympus Mons, and how it and the area surrounding it is supported.

Root is part of a team that is proposing a mission, known as the Martian Quantum Gravity (MaQuls) mission, to develop a detailed map of Mars’ gravity field.

His team has proposed using technology developed from the NASA missions GRAIL and GRACE, which were similar by design. One used satellites to orbit the Earth and Moon, while the other used spacecraft to measure Earth’s gravitational field and look at deviations.

Such data could help researchers learn of seasonal changes or ground water reservoirs on Mars, according to Dr. Lisa Wörner, who presented the mission during the recent meeting.

“Observations with MaQuIs would enable us to better explore the subsurface of Mars. This would help us to find out more about these mysterious hidden features and study ongoing mantle convection, as well as understand dynamic surface processes like atmospheric seasonal changes and the detection of ground water reservoirs,” she said.