MASSAPEQUA PARK, N.Y.—The first find was startling: a woman’s skeletal remains cast into the dunes along a remote Long Island highway.

Then came the shock.

Days after that discovery in December 2010, police discovered parts of three more women nearby on a spit of sand known as Gilgo Beach. The remains of six other people were found along several miles of the same parkway during the next few months. An 11th person, whose disappearance had spurred the initial search, was found dead by the highway in December 2011.

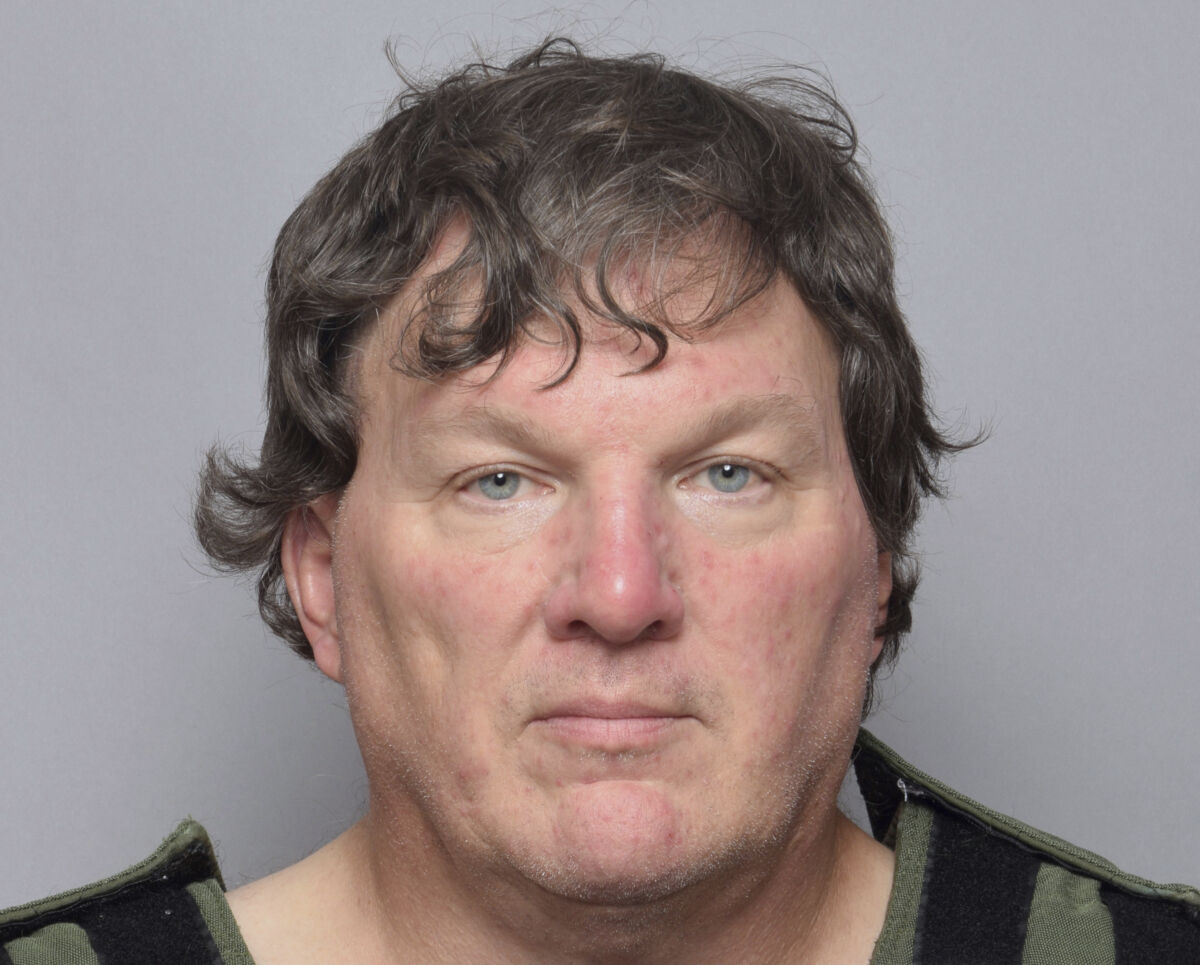

What became known as the Gilgo Beach murders—the victims mostly young women who had been sex workers—flummoxed investigators for over a dozen years. The case endured through five police commissioners, more than 1,000 tips, countless theories and supposed conspiracies. Then a fresh review last year tied an old clue, about a pickup truck linked to a victim’s disappearance, to a new name: Rex A. Heuermann.

Energized by the truck tidbit, investigators charted the calls and travels of multiple cellphones, picked apart email aliases, delved into search histories, and collected discarded bottles—and even a pizza crust—for advanced DNA testing, according to court papers.

On Friday, Mr. Heuermann was charged with murder in three of the killings, and prosecutors called him the prime suspect in a fourth.

“Since the discovery of the first victim, there’s been a lot of scrutiny and criticism regarding how this investigation was handled. I will tell you this: The investigators were never discouraged,” Suffolk County Police Commissioner Rodney Harrison said. He vowed they would continue working “until we bring justice to all the families involved.”

Mr. Heuermann, a 59-year-old architect, pleaded not guilty to multiple murder charges. He insists he “didn’t do this,” his lawyer Michael Brown said.

But police and prosecutors paint a picture of a scheming predator who outwardly maintained the life of a suburban professional, while secretly killing women when his wife was out of town.

“We are going to convict him, and we are going to hold him responsible for what he did,” Suffolk County District Attorney Ray Tierney declared.

Voice and email messages seeking comment were sent Friday and Saturday to various numbers and addresses associated with Mr. Heuermann and his family.

Mr. Heuermann used a victim’s cellphone to torment her relatives with calls—including one in which he said he’d killed her—and doggedly searched for information about the investigation while trying to obscure his identity online, according to prosecutors.

Among his searches: “Why hasn’t the long island serial killer been caught.”

The case began with a search for Shannan Gilbert, a sex worker who had called 911 as she ran from a client’s home, saying someone was chasing her. Police were looking for Gilbert in December 2010 when they stumbled upon the remains of someone else: Melissa Barthelemy, last seen alive the year before.

As the toll of victims grew and the search expanded, police used horses to reach the remote area, climbed firefighters’ ladders to see over poison ivy-infested thickets, scoured parking ticket records and got aerial surveillance photos from the FBI. Over the years, reward money was offered, FBI experts profiled the killer and evolving DNA techniques were used.

Harrison announced a new task force to work the case shortly after he became commissioner in January 2022. He’d been a high-ranking New York Police Department official and brought new energy and perspective to the investigation years after the Suffolk department’s former chief was arrested and went to prison in an unrelated case.

Mr. Tierney said a breakthrough came six weeks into the group’s work, when a New York State Police investigator used a database to determine that Mr. Heuermann owned an early-model Chevrolet Avalanche and lived in Massapequa Park, an area that had come into focus because of some victims’ cellphone activity.

The Avalanche was key because witnesses had told police that a man had parked one outside the home of victim Amber Costello the night before she died, and that the sex worker had arranged to meet that man again the next night, according to prosecutors’ court filing.

Using subpoenas and search warrants, investigators dug into Mr. Heuermann’s background. They learned that his cellphone had often been in the same general areas, around the same times, as prepaid anonymous cellphones that had been used to contact Barthelemy, Costello, and victim Megan Waterman, the court papers said. The “burner” phones and Mr. Heuerman’s phone sometimes even traveled together.

His phone’s location also roughly matched up with some places and times when a man used Barthelemy’s phone to call her relatives after her disappearance, according to the documents.

Combing Mr. Heuerman’s credit card records, investigators found payments to a dating site and followed that thread to uncover email addresses under fictitious names and more burner phones. The emails were linked to searches for violent pornography and information on the Gilgo Beach case, and to apparent selfies of Mr. Heuermann that were sent to arrange sexual trysts, court papers said.

The phones contacted massage parlors and sex workers as recently as this year. Mr. Heuermann was carrying one of the phones when arrested Thursday night, according to prosecutors.

Using advanced DNA testing not available early in the case, authorities also reexamined hairs found on a belt buckle, duct tape and a burlap restraint used in the killings.

Meanwhile, investigators employed more old-fashioned methods to snare a sample of Mr. Heuermann’s DNA: They tailed him and sifted through his garbage to pluck 11 bottles from his home bin and grab partially eaten pizza crusts that he’d tossed into a trash can on a Manhattan sidewalk.

The DNA from the pizza matched a hair found on burlap wrapped around one victim, and other hairs matched a relative of Mr. Heuermann’s who isn’t a suspect, investigators said. They believe he got the other person’s hair on him at home.

Mr. Heuermann has lived in the same ramshackle house since childhood, according to testimony he gave several years ago in one of several traffic-accident-related lawsuits he’s filed in the past decade. He graduated from the same local high school as actor Billy Baldwin, who tweeted Friday that news of his 1981 classmate’s arrest was “mind-boggling.”

After getting a bachelor’s degree from the New York Institute of Technology, Mr. Heuermann formed his architecture firm in 1994. He did most of his architectural work in New York City, with clients including city agencies, charities, airlines and major retailers, according to a company biography and the firm’s website.

In 2007, the city’s Department of Buildings audited multiple jobs involving Mr. Heuermann after an allegation that he falsely said a seven-story building was vacant when it was set to be renovated. The audits didn’t find any pattern of false filings or significant disregard for city regulations, and no disciplinary actions were taken, according to the department.

After a brief marriage in the early 1990s, Mr. Heuermann has been married since 1996 to wife Asa, with whom he has a daughter—a graphic artist—and a stepson, according to his 2018 testimony. His wife, he testified, dropped him off at a nearby train station in the mornings.

Neighbors puzzled at the rundown home with the overgrown shrubs in their tidy midst, and at the contrast between the house and the businessman who set off from it each weekday with suit and briefcase.

“It was,” neighbor Barry Auslander said, “weird.”

By Jennifer Peltz, Michael R. Sisak, and Jake Offenhartz