INDIAN ROCKS BEACH, Fla.—Aiden Bowles was stubborn, so even as Florida officials told residents of the barrier island north of St. Petersburg that Hurricane Helene’s storm surge could be deadly, the retired restaurant owner stayed put.

Caregiver Amanda Normand begged the 71-year-old widower to stay with her inland, but there had been many evacuation warnings over the years as hurricanes neared his Indian Rocks Beach home—the storm surge never got more than knee-high. As Helene and its strong winds pushed north in the Gulf of Mexico, he wasn’t worried—its eye was 100 miles offshore.

“He said, ‘It’s going to be fine. I’m going to go to bed,’” Normand said of their final phone call on the night of Sept. 26.

But it wasn’t fine. In that night’s darkness, a wall of water up to 8-feet high slammed ashore on the barrier islands. It swept into homes, forcing some who had ignored the evacuation orders to climb into upper floors, attics or onto their roofs to survive. Boats got dumped in streets, and cars dumped into the water.

Bowles and 11 others perished as Helene hit the Tampa Bay area harder than any hurricane in 103 years. By far the worst damage in the area happened in Pinellas County on the narrow, 20-mile string of barrier islands that stretch from St. Petersburg to Clearwater. Mansions, brightly colored single-family homes, apartments, mobile homes, restaurants, bars and shops were destroyed or heavily damaged in minutes.

“The water, it just came so fast,” said Dave Behringer, who rode out the storm in his home after telling his wife to flee. His neighborhood got hit with about 4 feet of water. “Even if you wanted to leave, there was no getting out.”

While the property damage was mostly unavoidable, there didn’t have to be any deaths—the National Hurricane Center issued its first storm surge warning two days before Helene arrived, telling the barrier islands’ residents they should pack up and get out. The relatively shallow waters of Florida’s Gulf Coast make it particularly vulnerable to storm surge and forecasters predicted Helene’s would hit Pinellas County hard.

“We really want people to take the warning seriously because their lives are seriously at risk,” Cody Fritz, leader of the hurricane center’s storm surge team, said, adding that warnings are never issued lightly.

Pinellas County echoed the warnings, issuing mandatory evacuation orders—but that doesn’t mean police officers force out residents. In Florida, mandatory evacuation orders simply mean that anyone who stays behind is on their own, and first responders aren’t required to risk their lives to save stragglers.

“We made our case. We told people what they needed to do, and they chose otherwise,” Sheriff Bob Gualtieri said. Still, his deputies did try to save residents, but the surge forced their boats and vehicles back.

The Tampa Bay area has been extremely lucky over the last century. Since the last major storm scored a direct hit in 1921, Tampa, St. Petersburg and their environs have grown from about 300,000 combined residents to more than 3 million today.

Tampa Bay has been in the crosshairs of many storms over the decades, but they always turn into the Florida peninsula south of the area or make a beeline north into the Panhandle.

Helene was never predicted to hit Tampa—it’s eye made landfall 180 miles north. But at more than 200-miles wide and winds whipping at nearly 140 mph near its core, it created surges that hit all along the Florida peninsula’s Gulf Coast. Most weren’t deadly, but on Pinellas’ barrier islands, the water wall came from all directions.

“It doesn’t require a storm making landfall directly on top of Tampa Bay or just to its north to cause a lot of surge problems, especially when you have a large storm like Helene,” said Philip Klotzbach, a hurricane researcher at Colorado State University.

It will take time for the islands to return to normal. In the 90-degree heat, residents spent this week piling water-logged furniture, appliances, cupboards and dry wall outside to be hauled away. Bulldozers pushed sand back onto the beach. Employees at stores and restaurants threw out what couldn’t be saved, while the owners figured out how and when they could reopen. Some might not.

Laura Rushmore, who has owned the Reds on the Boulevard bar for 20 years, might walk away. She cried as she described the damage. A cooler full of beer had been tossed on its side, the bar’s interior ruined. She isn’t sure what insurance will cover.

“It’s too much,” she said.

Then there are the deaths—the people can’t be replaced.

Frank Wright had been the outdoors type, perfect for living in Madeira Beach, a small barrier island community. But a few years ago, the 71-year-old got a degenerative autoimmune disease.

“He went from being pretty active, outside and everything, to being in a wheelchair,” his neighbor Mike Visnick said.

He thinks Wright probably believed he would be safe, given the prior warnings that didn’t pan out. But he drowned in the surge.

“It’s really sad to me how he died. He lived a good life. He loved the beach,” Visnick said.

Farther north in Honeymoon Mobile Home Park, retired hairdresser Patricia Mikos had never before tempted fate, her neighbor Georgia Marcum said. The beach community is onshore, but that area was also in the surge’s predicted path.

The 80-year-old always fled when hurricanes neared, so when Marcum left the park before the storm to care for her 95-year-old father, she was certain her friend would also leave.

But for some reason she didn’t and as the waters rose, Mikos found herself in trouble. She called a nearby friend. When he arrived, he told her, “Let’s get out of here,” according to Marcum. But when she went back into her home to get something, the water trapped her inside.

The friend “couldn’t get back in there. He’s not talking to nobody. He’s not even talking to us. I’m sure he blames himself,” Marcum said.

About 10 miles to the south in Indian Rocks Beach, two of Bowles’ neighbors, Donna Fagersten and Heather Anne Boles decided to ride out Helene in their homes as they had done with other storms.

Fagersten, 66, was four days from retiring after 35 years teaching, most recently second grade. In retirement, she would have time to watch the crime dramas she loved and spend time with her two sons, her friends and her cat.

Boles told WTVT-TV that when the water slammed ashore, she and Fagersten tried to drive away, but couldn’t. They fled into the home of Boles’ mother and rushed to the third floor.

After a bit, the storm seemed to weaken, so Fagersten decided to go home and check on her cat but got caught in the water. She couldn’t be saved. Her cat was found safe.

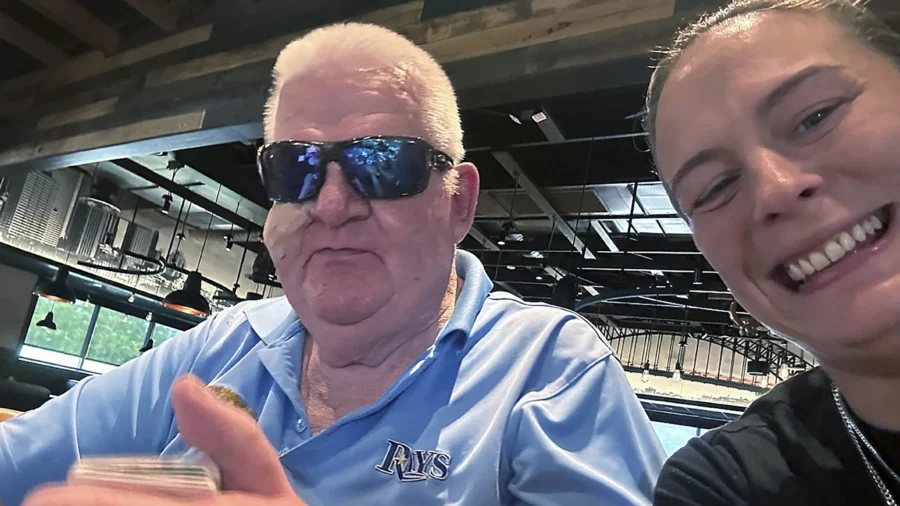

Earlier this week at Bowles’ wrecked home, Normand, 34, was cleaning up the mess Helene left behind. She had long worked for Bowles and his late wife, Sabrina, at the Salt Public House. They were beloved by their employees, she said.

“He was just very genuine. He was the best person I know on this earth. Just talking about it gives me goosebumps,” she said.

She became Bowles’ caregiver after his wife died two years ago and he retired. She took him to the doctor and bought his groceries. They were each other’s shoulder to cry on.

On the morning after the surge, Normand tried desperately to reach Bowles, but the bridge was blocked. She called one of his neighbors, who found his body.

“Every day I wake up thinking, ‘Was he calling for me? Was he like trying to get me or something?’” Normand said, her voice sometimes breaking. “I just hope that he wasn’t in pain.”

Her 6-year-old son considered Bowles to be a grandfather and didn’t understand what happened.

“He says to me, ‘Mommy we’re going to go get Mr. Bowles and open the doors and get all the water out,’” she said. “It just broke my heart.”

By David Fischer and Terry Spencer