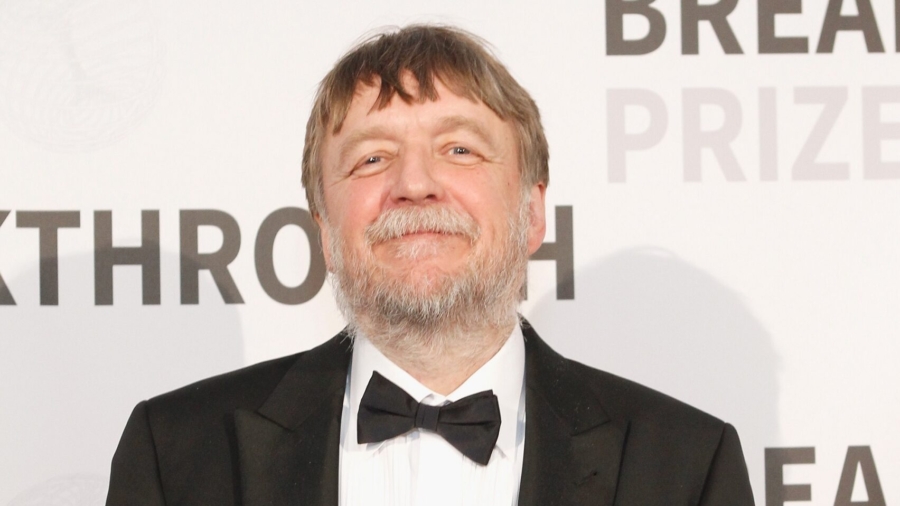

The celebrated Alzheimer’s Disease researcher John Hardy was among the British doctors and medical researchers honored by Queen Elizabeth II with knighthoods at the dawn of the new year. It was just the latest on a long list of prestigious awards Hardy has collected, including the Potamkin Prize for his work identifying genetic aspects of Alzheimer’s disease, the MetLife Prize, the Thudichum medal, the Robert A. Pritzker Prize, and the Breakthrough Prize.

In 2018, Hardy added the Brain Prize to his list of accolades. Awarded by the Danish Lundbeck Foundation, it is regularly referred to as the “Nobel of neuroscience.” Winners are assumed to be on the short list for the Nobels themselves.

Missing among all the flattering kudos and attendant news coverage has been any mention of the geneticist’s leading role in a conspiracy that held Alzheimer’s research hostage to fraudulently acquired gene patents. The sordid affair mired efforts to find a cure in tangled, resource-sapping litigation. The last of the courthouse wrangling that began in 2003 wouldn’t be resolved for more than a decade—a resolution that came with a ringing rebuke from the bench expressing the judge’s outrage at the scheme, the schemers, and the damage they caused.

Yet until now, the full details of the deceptions of Hardy and his accomplices have not been widely reported. Some of them are consigned to scholarly literature and other startling ones are found in overlooked testimony from the prolonged litigation, which documents one of the most celebrated scientists of our time admitting under oath that he lied and committed academic fraud, and confessing that he was ashamed.

The story—which also ensnared one of the world’s most prominent woman scientists, who admitted under oath that she too lied, pressured by Hardy—emerges at a time when the credibility of august scientific authorities is being sorely challenged on other fronts, not least during the coronavirus pandemic.

John Hardy is credited with discovering genetic mutations that suggested Alzheimer’s disease may be caused by an excess of a protein called “amyloid” building up in the brain. His “amyloid cascade hypothesis” has dominated scientific debate on Alzheimer’s for 30 years. It made Hardy famous in scientific circles, and “paved the way for many of the drugs in clinical trials today,” according to the British nonprofit Alzheimer’s Research UK. Among those potential therapies being tested is the anti-amyloid compound aducanumab, approved in the United States last summer. Hardy consults with the Japanese pharmaceutical company Eisai, which has brought aducanumab to market under the brand name Aduhelm.

In the glow of what initially appeared to be the drug’s success, media were hardly restrained about the prospects, with the news magazine The Week speculating that the new drug had brought Hardy “significantly closer to a Nobel.”

Overshadowed is the episode that makes Hardy a problematic ambassador for science: In the 1990s he participated in elaborate machinations to misrepresent the authorship of medical discoveries. He led an effort to defraud universities in Britain and the United States of millions of dollars, a scheme that involved empowering a patent “troll” to shake down Alzheimer’s researchers by demanding royalties on bogus gene patents.

Hardy’s dissembling began with a discovery, early in his career, that made his name. “In a leap forward in the search for a cause of Alzheimer’s disease,” the New York Times reported enthusiastically in February 1991, “researchers have discovered that a pinpoint mutation in a single gene can cause this progressive neurological illness.” The Times went so far as to claim a cure could be imminent.

The late 80s and early 90s were banner years for genetic research into the brain. Teams from California, Boston, London, and elsewhere were racing against one another, using new gene-mapping techniques to find the genetic mutation(s) believed to be responsible for early-onset Alzheimer’s. In particular, doctors were searching for the genetic sources of the brain-clogging amyloid plaques and “tau-containing neurofibrillary tangles” found in Alzheimer’s patients.

The publicity—and the suggestion a cure might soon be found—brought pharmaceutical companies to St. Mary’s Hospital at Imperial College London, looking to turn the Hardy team’s findings into therapies. Imperial had an office, Imperial Exploitation Limited (IMPEL), devoted to commercializing faculty discoveries. It operated under the U.K. Patents Act of 1977: In British law, the employer, not the employee, enjoys ownership of any invention created in the “normal course of employment duties.”

IMPEL made a deal with the biotech firm Athena Neurosciences, a bargain Hardy likened to the sort of deal on “Antiques Roadshow” when a hapless seller lets a Rembrandt go for $20. “I was just exasperated,” Hardy would later testify, adding that he “expressed that exasperation in words that would not be suitable for a courtroom.”

That exasperation was shared by some of the doctoral students and post-docs working for Hardy in his lab. Their pique turned to anger when Hardy attended an event at which Athena pitched investors. Hardy said the head of the company bragged he had acquired intellectual property from Imperial College at a fraction of its $10 million value. “I was very angry that we had made such a terrible agreement only two months earlier,” Hardy recounted. “Now here was this CEO saying that the stuff was worth a fortune and that he had paid a pittance.”

Stoking the researchers’ anger was an American businessman, Ronald Sexton, who befriended the Hardy lab crowd, buying them expensive, fancy hotel meals, commiserating with them about how unfair IMPEL had been to them, providing (and paying for) lawyers to represent them, and suggesting ways they could throw wrenches into the Athena deal.

“Mr. Sexton encouraged us to refuse to sign inventor’s paperwork and to create other problems for Imperial College and its agreement with Athena,” Hardy said in a sworn statement entered into evidence in a U.S. federal court years later. “Mr. Sexton advised us that by creating problems for Imperial College regarding the Athena Agreement, we could also create problems for Athena and thereby force Imperial College and Athena to renegotiate the Agreement.” Sexton urged Hardy and researchers Michael Mullan and Alison Goate to keep any new breakthroughs on the QT. “Mr. Sexton encouraged us not to disclose to Imperial or Athena any discoveries of additional mutations,” Hardy admitted.

A litigious businessman based in Kansas City, Sexton invested in many things, including gemstones, residential foreclosures, and corporate jets. He had no background in medical research. But he did have an idea for how to monetize the Hardy team’s discoveries: He would set up a company to hold the intellectual property in the form of patents on the mutated genes Hardy’s group had found. Anyone who wanted to do research involving the DNA would be required to pay royalties to Sexton. Hardy and his team would be paid handsomely.

Hardy, Mullan, and Sexton devised a plan to scuttle the Athena deal. Mullan, a young medical doctor pursuing a PhD, had joined the Hardy lab in October 1988. What if Mullan had been responsible for key innovations that contributed to the discovery of the London mutation? And what if he had made those advances on his own before joining Hardy’s lab? The case could then be made that Imperial College had no rights to the London mutation because the discovery had been independently made by Mullan before he went to work at the university.

There was a problem with the origin story crediting Mullan. It was phony. Not only would Hardy and Mullan have to deceive Imperial College, they would have to get other young researchers, such as Alison Goate, to lie as well. Nor would these be trivial fibs. It would mean falsifying in writing when and how data was collected and analyzed, a not insignificant act of fraud.

Goate seems a longshot to engage in scientific misconduct. She now chairs the Department of Genetics and Genomic Sciences at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai hospital in Manhattan. She has been awarded the Khalid Iqbal Lifetime Achievement Award for her work on Alzheimer’s, and she is the founding director of the Loeb Center of Alzheimer’s Disease at Mount Sinai. But in 1992, she was one of the young researchers working for Hardy (and shared one of his accolades). Goate says he pressured her into making blatant misrepresentations of her own lab research.

Goate signed a copy of a letter drafted by Hardy asserting that no work had been done on the London mutation at St. Mary’s, claiming instead that the discovery was Mullan’s. Twenty years later that letter was entered into evidence in a federal civil lawsuit in the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, where Sexton’s intellectual property holding company was trying to enforce patents against Avid Pharmaceuticals and the University of Pennsylvania. “Is this letter a true and accurate description of Dr. Mullan’s role in the discovery of the London Mutation?” she was asked under oath.

“No.” Goate conceded. “It’s revisionist history. It was rewriting and embellishing the events in order to emphasize any role that Dr. Mullan had had while he was not at Imperial College.”

Did she know at the time “that this letter that you signed and sent to your employer in 1992 was in sum and substance false?”

“I did,” Goate admitted. “I am not proud of what I did. I did so unwillingly.” Hardy, Mullan, and Sexton, she testified, pressured her to make the false claims.

“It was all a lie,” Goate said. “I felt really uncomfortable about telling lies to my employer.” She signed the letter “under duress,” but nonetheless admitted she participated in a “scheme to cheat the Imperial College of London.” RealClearInvestigations contacted Goate and asked her for more details. She replied: “I don’t think my memory of the events that occurred then is strong enough for me to answer your questions beyond the testimony you have.”

When it was Hardy’s turn to be questioned in front of the jury, he expressed little of the remorse that characterized Goate’s testimony. A lawyer pointed him to the key language in a letter he had written to IMPEL: “I can assure you and Athena that none of the work reported in the paper was carried out here at St. Mary’s.”

“Is that a true statement?” the lawyer asked.

“No.”

“How do you know it’s not true?”

“I know it’s not true,” Hardy said. “I mean, it’s a lie I told.”

This article was written by Eric Felten for RealClearInvestigations.