For some special interests, a fading coronavirus pandemic poses a problem, but not always an insurmountable one.

Big Labor and its acolytes cite the virus as a compelling reason for doubling the minimum wage and forcing businesses to provide more paid sick leave, while the Biden administration is using the pandemic as part of its justification for overhauling immigration toward eventual amnesty for undocumented migrants.

Meanwhile, the left-leaning Brookings Institution has successfully persuaded the federal government to allocate more money to child-care programs in the name of pandemic safety.

These changes have long been on the policy wish lists of advocates, but in a time of pandemic they evoke words widely attributed to Winston Churchill: “Never let a good crisis go to waste.” Or as a headline this week might sum up a new urgency: “The U.S. Is Edging Toward Normal, Alarming Some Officials.”

Several states and municipalities struck while the virus was hot by signing off on COVID-connected sick leave rules, and more are considering broadening their policies.

In Colorado, lawmakers passed a permanent change to the state’s so-called leave act, citing the pandemic. It requires businesses with 16 employees or more to allow workers in the state to accrue up to six paid sick days annually beginning in 2021.

Advocates deny using the virus as an opportunity, instead contending it merely further exposed problems long present that should at last be addressed.

“What COVID did was shed light on what workers have always had to deal with,” said Kim Cordova, president of the United Food and Commercial Workers Local 7, a union that represents 30,000 private sector workers in Colorado and Wyoming.

“We are not piggybacking on COVID,” Cordova said. “We’ve advocated for paid leave for all these years, and this [pandemic] is a big reason why.”

The changes to sick leave that the union helped push through the Colorado statehouse will outlast the pandemic, she said, “but there will always be some sort of illness to deal with in the future.”

“This is a once-in-several-generations opportunity to reset our policies and our culture to better support families and caregivers who have been on the frontlines of this pandemic in so many ways,” Ai-jen Poo, executive director of the union-allied National Domestic Workers Alliance, said in Facebook statement. Her group is seeking universal paid leave for employees, and this is the perfect time, she said.

“We must not let this opportunity go to waste,” wrote Poo, who did not respond to an interview request.

Part of the pending federal $1.9 trillion COVID-19 relief package included a provision – sidelined for now due to procedural rules — to increase the minimum wage from $7.25 an hour to $15 over the next four years. It illustrates the momentum to commit to spending beyond the current crisis.

The gradual minimum-wage increases extended “far past when the pandemic ends,” said Skip Estes, associate director of the American Legislative Exchange Council’s Center for State Fiscal Reform. “COVID is this window dressing to push through this stack of legislative priorities. The minimum-wage increase is not linked to the virus at all.”

Yes it is, said Brigette Dumais, a political organizer with a New York chapter of the Service Employees International Union, agreeing with her labor colleagues. “Essential workers … are on the front lines of this pandemic, and the vast majority of them are making under $15 an hour,” she argued during a virtual rally the union hosted in June, according to NPR.

Dumais did not respond to texts and calls seeking comment.

In addition to mandatory paid sick-leave policies and minimum-wage increases, the drive to overhaul immigration in line with Democrat priorities is also being tethered to the pandemic.

In backing President Biden’s fast-tracking of an immigration overhaul, SEIU International Executive Vice President Rocio Sáenz said in a press release in February that the pandemic is a compelling reason to grant the undocumented amnesty.

“It is critical that this bill or other bills … provide a roadmap to citizenship for large numbers of immigrants,” Sáenz said in the statement. “We also strongly support the idea of legalizing essential workers as a necessary part of COVID recovery.” Under current policies, employers are struggling to find workers, with job openings at a five-month high.

Others claim that amnesty would add to the tax base, making it easier for states to recover from the economic woes caused by the pandemic.

Arthur Herman, a historian and director of the Quantum Alliance Initiative at Hudson Institute, said the politicization of COVID relief recalls the financial meltdown in 2008 and 2009 and its “big infrastructure bill, with the overwhelming bulk of it going to pay off political supporters” – especially those in organized labor and higher education.

The federal COVID relief bill includes specific allocations to two Washington, D.C., schools — Gallaudet University, which serves the deaf and hearing impaired; and Howard University, including money to be used for student aid with no time specifications.

Also included are $10 million in Susan Harwood Training Grants, which provide funding to nonprofits including labor associations and higher education. Last year’s 89 Harwood grants included 16 related directly to the pandemic.

“You could say Democrats are going back to the playbook they used in 2009,” Herman said.

The Brookings Institution in October demanded more money be spent on child care teachers in the wake of COVID “to ensure the immediate safety and well-being of these educators, and the children, families, and communities they serve.”

Its wish was granted: A stimulus package passed in December gave $10 billion to the child care industry.

A Brookings spokeswoman did not respond to an interview request.

In some cases, invoking the crisis is an integral part the argument, “but it’s not necessarily an exploitation of it,” said James Hohman, director of fiscal policy at the Mackinac Center for Public Policy.

“It only seems like an exploitation of a crisis if they argue that permanent policy changes are necessary to solve temporary problems,” he said.

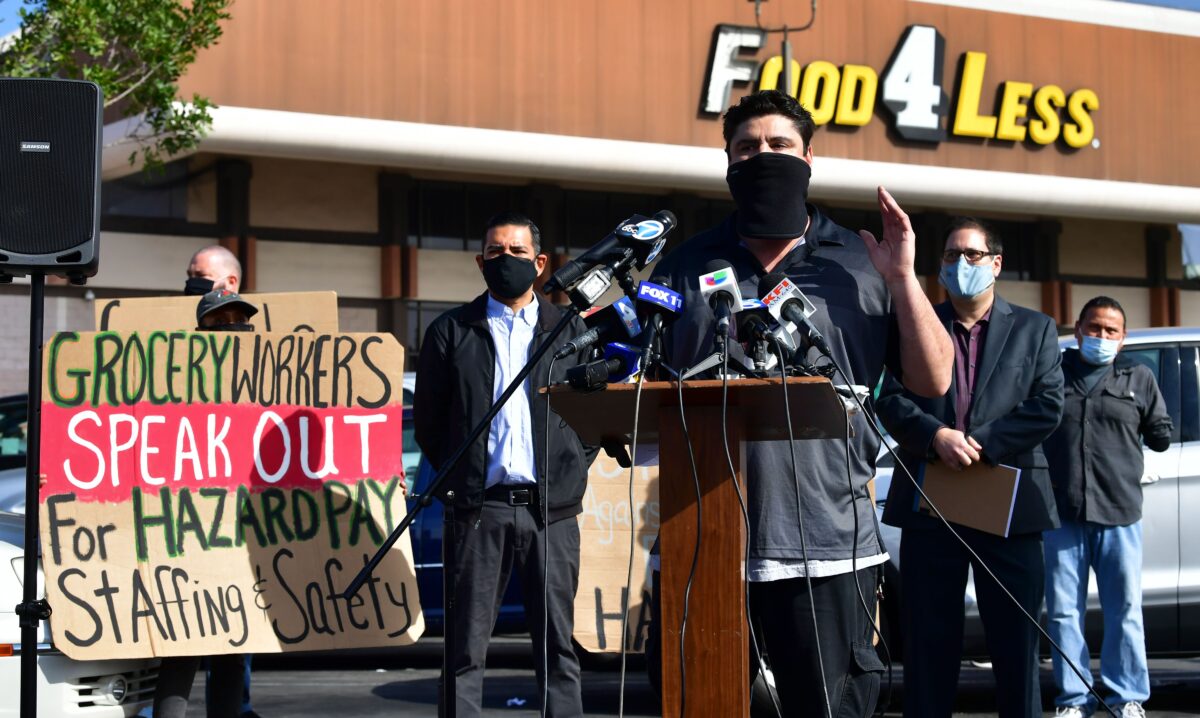

A crusade for COVID hazard pay launched in the fall and led by the United Food and Commercial Workers’ union is taking shape in several West Coast cities including Seattle, Long Beach, Calif., and Los Angeles.

Most language regarding hazard pay requires the declaration of a public health emergency before the pay kicks in. Given the pandemic, such declarations will be much easier to come by in the future, said Merrill Matthews, resident scholar with the conservative Institute for Policy Innovation.

He likened the situation to weather alarmism now common as a result of Hurricane Katrina in 2005, when a failure to fully warn and prepare Louisianans was blamed for avoidable deaths.

“So there is overreaction, and that’s somewhat understandable,” Matthews said. “You don’t want to be caught not doing enough. And I think this will be true for any new virulent flu strain in next few years.”

This article was written by Steve Miller for RealClearInvestigations.