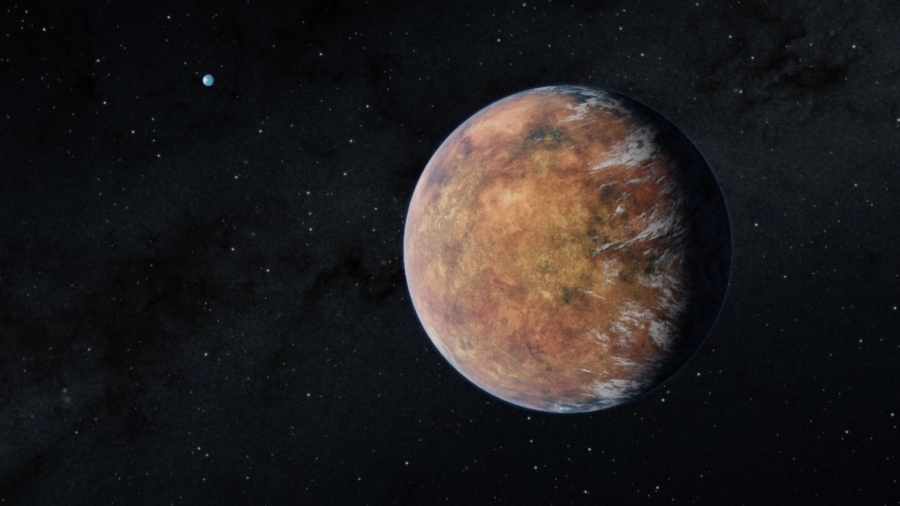

A team of NASA scientists discovered another Earth-sized exoplanet orbiting in its star’s habitable zone that could potentially retain liquid water, the U.S. space agency announced on Tuesday.

The planet—called “TOI 700 e”—is about 95 percent of Earth’s size and likely rocky. It was spotted in a system in the southern hemisphere about 100 light-years away from Earth while orbiting a small, cool M dwarf star dubbed “TOI 700.”

In 2020, scientists discovered the system’s first Earth-sized planet called “TOI 700 d.” There are four known planets in total orbiting TOI 700, although only two—which are e and d—exist in the star’s habitable zone.

“This is one of only a few systems with multiple, small, habitable-zone planets that we know of,” Emily Gilbert, a postdoctoral fellow at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California, said in a statement on Tuesday.

“That makes the TOI 700 system an exciting prospect for additional follow-up,” Gilbert added, noting that the newly discovered planet is about 10 percent smaller than its sibling, TOI 700 d.

Scientists’ latest discovery also revealed how additional research with NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) can aid them in locating “smaller and smaller worlds.”

The other two planets that were previously found in the system are called “TOI 700 b” and “TOI 700 c.”

Planet b is about 90 percent of Earth’s size and orbits the star every 10 days, while planet c is more than 2.5 times the size of Earth and completes an orbit every 16 days. Both of these planets are likely tidally locked, which means they always show the same side to the star, similar to how the same side of the Moon is always facing Earth.

“Scientists define the optimistic habitable zone as the range of distances from a star where liquid surface water could be present at some point in a planet’s history,” NASA stated. “This area extends to either side of the conservative habitable zone, the range where researchers hypothesize liquid water could exist over most of the planet’s lifetime.”

TESS Mission

NASA’s planet-hunting TESS mission was launched in April 2018. Since then, TESS’s sensitive cameras have monitored large swaths of the sky for about 27 days at a time, tracking changes in stellar brightness caused by a planet crossing in front of its star, called transits.

In 2018, TESS began to observe the southern sky before turning to the northern sky. In 2020, the mission returned its focus to the southern sky for additional observations, which allowed them to locate smaller planets such as its latest discovery, TOI 700 e, in the TOI 700 system.

“If the star was a little closer or the planet a little bigger, we might have been able to spot TOI 700 e in the first year of TESS data,” said Ben Hord, a doctoral candidate at the University of Maryland and a graduate researcher at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. “But the signal was so faint that we needed the additional year of transit observations to identify it.”

Since TESS’s launch, it has scanned over 200,000 of the nearest and brightest stars and has created imaging for about 75 percent of the sky.

Over the course of two years, the four wide-field cameras on board stared at different sectors of the sky for days at a time. This has enabled scientists to survey the entire southern hemisphere sky in the first year and the northern hemisphere sky in the second year.

“TESS just completed its second year of northern sky observations,” Allison Youngblood, a research astrophysicist and the TESS deputy project scientist at Goddard, said in Tuesday’s statement. “We’re looking forward to the other exciting discoveries hidden in the mission’s treasure trove of data.”