Jiang Zemin’s days are numbered. It is only a question of when, not if, the former head of the Chinese Communist Party will be arrested. Jiang officially ran the Chinese regime for more than a decade, and for another decade he was the puppet master behind the scenes who often controlled events. During those decades Jiang did incalculable damage to China. At this moment when Jiang’s era is about to end, Epoch Times here republishes in serial form “Anything for Power: The Real Story of Jiang Zemin,” first published in English in 2011. The reader can come to understand better the career of this pivotal figure in today’s China.

The full series is available here.

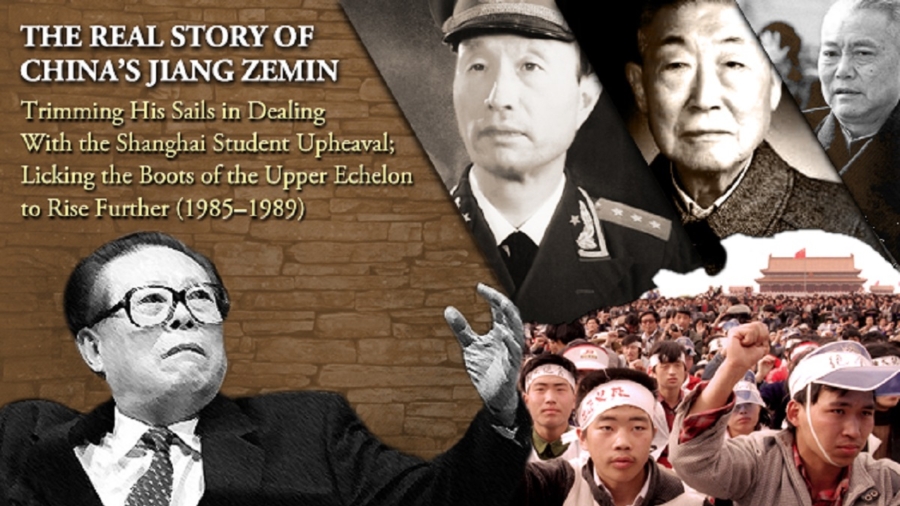

Chapter 4: Trimming His Sails in Dealing With the Shanghai Student Upheaval; Licking the Boots of the Upper Echelon to Rise Further (1985-1989)

1. Working His Connections and Fawning on Key Personnel to Become Shanghai’s Leader

It’s as if Jiang Zemin has an indissoluble bond with Shanghai. Though he was a traitor in Nanjing City, his transfer to Shanghai Jiaotong University allowed him to conceal his traitorous past. His performance as he worked in the Ministry of Electronics Industry was only mediocre, yet he became Mayor and Party Committee Secretary of Shanghai Municipality. That gave Jiang an opportunity to feel what it was like to crush dissent with violence, as he suppressed the outspoken students there. After ascending to the position of General Secretary of the CCP, Jiang spared no efforts in establishing the aptly named “Shanghai Gang” to ensure the stability of his power. Tellingly, as soon as the SARS crisis arose Jiang retreated to Shanghai and went into hiding.

Jiang Zemin’s receiving a position in Shanghai in 1985 was the result of strong endorsement from Chen Guodong, the Party Committee Secretary of Shanghai Municipality, and Shanghai’s Mayor, Wang Daohan. Chen and Wang did not act solely for the sake of the state, but also to reciprocate the goodwill of [Jiang’s uncle,] Jiang Shangqing.

Jiang Shangqing was once Wang Daohan’s immediate superior. During the initial period of the War of Resistance against Japan, Wang Daohan had held the post of Jiashan County CCP Committee Secretary in Anhui Province; he reported directly to Jiang Shangqing. Chen Guodong, meanwhile, had become Anhui Lingbi County’s Magistrate due to Jiang Shangqing’s strong recommendation.

Forty years later, those two CCP cadres with backgrounds in the East China system were both made high provincial officials. Feeling indebted, they gave maximum support to Jiang Zemin, the supposed foster child of the deceased Jiang Shangqing.

When we look at the histories of the people who supported Jiang Zemin, we can see that it was not due to his abilities that Jiang rose to power, but rather, to his connection to a deceased man that purportedly adopted him.

Every winter CCP elders retreat to Shanghai. This fact gave Jiang many chances to curry favor with influential officials and move closer to fulfilling his political ambitions. The abilities of Chen Yun and Li Xiannian to influence, respectively, the CCP’s Central Committee and State Council members, provided Jiang with the opportunity to maneuver his ascent.

Chen Yun was born in Shanghai. After the Zunyi Meeting, while the Red Army was fleeing to the North, Chen was ordered to reinstate the CCP’s underground activities in Shanghai. After the CCP came to power and established its government, Chen, who had simultaneously held the position of Secretary of the Central Committee Secretariat and Deputy Premier of the State Administrative Council (now known as the State Council), was also made Director of the country’s Financial and Economic Committee. Virtually all cadres closely associated with Chen and who supported a planned economy were so-called “leftists” and politically conservative. Chen’s relative Song Renqiong, who later held the post of Minister of the Organization Department of the CCP Central Committee, along with Chen’s student Yao Yilin and the cadres in the East China system, were virtually all from Chen’s clique. The clique also included Chen’s aid, Zeng Shan, who was the Financial and Economic Committee Director of the East China region and the father of Zeng Qinghong, a current member of the Standing Committee of the Politburo. Others who were once in office under Chen Yun included people like Chen Guodong, Wang Daohan, and the Chief of the Organization Department of the East China Bureau, Hu Lijiao. Li Xiannian, however, was constantly entangled in conflicts with Deng Xiaoping, asserting his reservations about, and later rejection of, Deng’s economic “reform and opening-up” policies.

Although Deng Xiaoping was the core leader of the second generation leadership, Chen Yun and Li Xiannian constantly held him back as they struggled for power. Neither side, however, ever achieved an absolutely dominant position. Jiang Zemin, who was at the time Mayor of Shanghai, attended to the needs of and kissed up to both Chen and Li, singing the praises of their economic plans. But at the same time, Jiang didn’t dare to offend Deng Xiaoping. And in front of Hu Yaobang and Zhao Ziyang the conservative Jiang Zemin would morph into a completely different person, for he felt it necessary to go along with and express outwardly an interest in economic reform.

2. A First Sweet Taste of Success in Suppressing Dissent With Violence

Jiang Zemin came to Shanghai during a time when urban reform was just beginning. Citizens were faced with prices of non-staple food products and other daily basic necessities that unexpectedly rose 17 percent within just one year. The CCP claimed that the rise in costs was just a precursor to an economic breakthrough. Not only were there no breakthroughs in the price of goods, however, but the high prices even led to public discontent and gave rise to a student movement. The students demanded that the government solve two problems: the increase in living costs and the corruption of government officials.

At that time, it was Hu Yaobang who presided over the CCP Central Committee, so, naturally, Jiang Zemin presented himself as being part of the reformist camp. Jiang went to a university to make a speech to more than 10,000 teachers and students. There he acknowledged that the rise in prices was beyond expectation but explained that the market economy would ultimately stabilize the prices, making them reasonable. The students believed Jiang at the time. Meanwhile, far away in Beijing was Hu Yaobang, who had begun actively pushing for political reform.

A series of significant events took place in 1986. In July, not long after doing graduate study at Princeton University in the U.S., the Vice President of the University of Science and Technology of China (in Anhui Province), Fang Lizhi, gave a series of speeches advocating democratic principles. In September, Taiwan’s first opposition party, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), founded 14 years earlier, won the general election and set the stage for political change in the Republic of China (Taiwan). The news was broadcast on Voice of America and heard by many students inside China. Those who were inspired by the idea of democracy were particularly excited after learning that Taiwan, having the same language and racial background as Mainland China, could form an opposition party.

The end of 1986 was the breaking point that prompted students to begin demonstrating. Setting them off was a stipulation by the Party Committee of the University of Science and Technology that undergraduate and graduate students were not allowed to run against the designated candidates for the People’s Representative positions in the elections in Anhui Province. In early December, more than 10,000 students from the university took to the streets twice to demonstrate. The news spread to Shanghai, which led to an expansion of the movement: students from Shanghai Tongji University and Shanghai Jiaotong University took to the streets in succession in response, calling for democracy, freedom, equality, and the abolition of autocratic dictatorship. The outcry later swept across Beijing and all over the country.

Students in Shanghai demanded dialogue with Jiang Zemin as well as, among other things, political reform, freedom of the press, and a loosening of governmental controls. On Dec. 8 of that year, Jiang and the Minister of Propaganda of the Shanghai Municipal Party Committee held a dialogue at Shanghai Jiaotong University with the students. What unfolded was dramatic in several regards.

Jiang Zemin stepped onto the podium, a sheet of paper in hand. He put on his thick glasses, unfolded his paper, and proceeded to speak about the achievements of the five-year economic plans. The students, however, were noticeably disinterested—the 3,000-plus students booed and hissed at Jiang. An irate Jiang looked up, sneered, and stared at the students, trying to identify the perpetrators. The students kept booing, unfazed. Some even shouted, “That plan of yours, we’ve been reading about it in the newspapers and seeing it on TV every day. This time you should listen to us!” Other students began shouting slogans.

Jiang Zemin, with sternness in his voice, pointed at the most boisterous student and said, “Jeering at me won’t get you anywhere. Let me tell you, I’ve seen plenty of upheavals! What’s your name? I dare you to come up to the podium. I dare you to make a speech!”

To Jiang’s surprise, the student did get up and walk up to the podium. He took the microphone and began talking confidently about his views on democracy. Then about 10 other students sprang up and went to the podium, standing face to face with Jiang, ready to debate. Jiang’s legs began to shake as things escalated. The students demanded freedom of the press, open and unbiased reports on their marches and demonstrations, and open debates in the form of large posters. The audience directed its attention to the students making the speeches.

Most shocking to Jiang was that the students went so far as to ask an extremely touchy question: “How did you become mayor?” Jiang smiled awkwardly in response as he retreated to the edge of the platform. When people had turned their attention away from him, Jiang signaled to the Minister of Propaganda, Chen Zhili, to take pictures of each student who came up to the podium. He wanted to take revenge on them later.

After the students’ emotionally-charged speeches it was finally Jiang’s turn to speak. He said, “As soon as I entered the campus, I saw your big posters.” Jiang tried hard to force a smile and went on to say, “You want to set up a government ‘of the people, by the people, and for the people.’ That is from Lincoln’s Gettysburg address, given on Nov. 19, 1863 to commemorate the martyrs of the American Civil War. Now I want to ask you, which of you can recite the address verbatim?”

The rowdy students were silent, wondering what tricks Jiang had up his sleeve. Faced with the students’ silence, Jiang, accustomed to the use of showmanship to distract from real issues, regained his confidence. He plucked up his courage, cleared his throat, and began to recite loudly, in English, the preamble of the U.S. Constitution and then Lincoln’s 1863 Gettysburg Address. The night before he had gone over each time and again so as to commit them to memory.

After the Cultural Revolution and at the initial stage of the reform and opening up period, students’ proficiency in English was, to be sure, in general not that high. Jiang Zemin prattled on with his recitation until he could recite no more. With a triumphant look he asked, “Did you understand that? I tell you, the situation in China is different from that in America…” When Jiang then began to ramble about how the leadership of the Party would be necessary for democracy, a student shouted at the top of his lungs, “We want to have the freedom to march and demonstrate now—as the Constitution guarantees! And to have news reported freely!” Jiang retracted his forced smile. With a fierce look that camouflaged the faint heart within, Jiang added, “Whoever blocks traffic and sabotages production is obstructing reforms, and therefore must bear the political consequences!” The students, bowed neither by persuasion or threat, remained fervent in their defiance of Jiang Zemin even though they had lost the microphone.

The afternoon’s meeting lasted for over three hours. As the atmosphere grew only increasingly more tense, Jiang lied and said that he had an appointment concerning foreign affairs and had to leave. Panic-stricken and eager to escape, on his way out Jiang accidentally bumped his head on a partially opened door. Though the cut was not deep it bled much. Jiang couldn’t stand the thought of waiting there, on the scene, to have his wound dressed, and so he used his hands to cover his forehead, hurriedly walked out, got into his car, and slipped away. Jiang’s panicked exit was for quite some time the standing joke among students.

It was surprising that, as mayor of Shanghai, the first thing Jiang did upon returning to his office was to make a phone call to the Secretary of the Party Committee of Shanghai Jiaotong University, He Yousheng. Jiang instructed He to go to Chen Zhili and collect the photos of students from that afternoon. Jiang urged him repeatedly to uncover the students’ names and class years. He Yousheng realized the seriousness of the matter, and repeatedly assured Jiang he would act accordingly.

Immediately afterwards Jiang Zemin instructed that, since Shanghai Jiaotong University was engaged in “bourgeois liberalization,” it was to shut down all student organizations and publications; only dance parties would be allowed henceforth. So it was that Jiang distracted people from their concerns over democracy and human rights by satisfying their more base desires—a method he has continued to use through the present. And the tactic proved quite effective. When the student movement started in 1989, students in different parts of the country marched and organized like wildfire. The students at Shanghai Jiaotong University, however, closed their doors and held dance parties all through the night, as they had once before. Not until Beijing students began a hunger strike on May 13, 1989, did many university students in Shanghai come out to march and express support. But the students at Shanghai Jiaotong University, now indifferent, continued to be preoccupied, holding dance parties daily. It was only when the government imposed martial law on May 19, 1989, that the students of Jiaotong University came out in droves to join the large-scale marches.

The day after Jiang Zemin’s 1986 “dialogue” with the students at Jiaotong University, the students of Shanghai took to the streets and gathered at the People’s Square, marching all the way to the city government and demanding further dialogue with Jiang. Their request was granted, but the meeting, from start to finish, was no different from that of the previous day. Jiang had learned from the first encounter and used it to his advantage the second time around. He quickly ordered 2,000 police to stand by at the Square and await his command. Jiang this time, enjoying the protection of the armed forces, was no longer full of forced smiles. He played tough and refused to give an inch—a chameleon-like change from only the day before. The dialogue ended in deadlock and the police were used to disperse students by force; the most rebellious were whisked off by bus. The students dispersed in an uproar. To Jiang the episode was a taste of sweet success—success in using political might and force to suppress dissidents.

The highly vindictive Jiang would never condone anyone who failed to comply with his demands, much less students who had defied him and embarrassed him before a crowd. The students whose photos were taken by Chen Zhili were not in the same class year and thus graduated at different times. In those days, China had a system whereby the government allocated college graduates to different locations. Jiang Zemin—the mayor—personally involved himself this time in the petty work of following up to see where those students were sent. He was not satisfied until each of the students who had spited him were sent off to the most remote and poverty-stricken areas of China.

3. Trying to Topple Hu Behind the Scenes, Delivering a Cake on a Snowy Night

There is a general rule that almost everyone in political circles knows: the more ruthless a person is with regard to his subordinates and the public, the more he will toady to his superiors. The fact is, these two seemingly-at-odds behaviors are meant to achieve one shared purpose: to seize more power and gain broader control.

Being the mayor of Shanghai, Jiang Zemin had an advantage in terms of advancing his political career. Namely, Shanghai was a favorite recreation spot for several senior CCP heavyweights. It would have taken a lot of effort for Jiang to travel all the way to Beijing, and much begging and pleading would have been required to gain an audience with figures of their stature. And even then it might not have worked. Little would Jiang, then, pass up a chance to toady when these influential leaders came town. It was a golden opportunity, he felt. His antics with the visiting leaders were like his recitation of the Gettysburg Address to student democracy activists: he won their affection and trust through rather deceptive means.

Officials that don’t have political accomplishments and who manage to rise through the ranks have been known to trample others to achieve their goals. Jiang Zemin fits perfectly into this category.

After the student movement ended, Deng Xiaoping published his speech of Dec. 30, 1986, called, “Take a Clear-Cut Stand Against Bourgeois Liberalization.” In it he stated, “A rumor is going around Shanghai to the effect that there is disagreement in the Central Committee as to whether we should uphold the Four Cardinal Principles and oppose liberalization, and that there is therefore a layer of protection. That’s why people in Shanghai are taking a wait-and-see attitude towards the disturbances.” Jiang Zemin read Deng Xiaoping’s speech the day after it was published and realized that Hu Yaobang’s reformist ideas and the CCP’s conservative bent were incompatible. Chen Yun, Li Xiannian, and their clique had long wanted to get rid of Hu, but it was Deng Xiaoping who had stood in the way by sustaining Hu politically. Yet now that Deng had publicly declared his displeasure with what one could describe as Hu’s inefficiency in dealing with anti-liberalization, the Central Committee’s inclination to purge him gradually intensified.

Deng’s speech was to Jiang pure treasure. Jiang thought that at a critical time such as then, it was imperative that he declare a completely identical stance as the Central Committee. But he was growing dejected over the lack of opportunity to speak with Deng Xiaoping or other senior statesmen about the matter.

Coincidentally in the winter of that year State Chairman Li Xiannian went to Shanghai and stayed at the city’s guesthouse. One evening Li summoned Jiang and the two had dinner together. He told Jiang that he was celebrating a birthday on that day. Even though the people in Shanghai were having a hard time feeding their families after only two years of Jiang’s tenure as mayor, Jiang had other things on his mind. He was puzzled over something. He had spared no effort in memorizing by heart each birthday of the senior members of the Central Committee. So how was it Li Xiannian was celebrating his birthday in winter when he was born on June 23, 1909?

That was before the phrase “keeping a mistress” (bao’ernai) was part of the Chinese lexicon. But according to The Private Life of Chairman Mao, a book written by Mao’s personal physician, extramarital affairs and promiscuity were common then among senior officials. Some had said that Peng Dehuai was purged from his position not because of the Great Leap Forward, but because he had opposed the Zhongnanhai Performing Arts Troupe. Peng had publicly said, “Although I never dance, I am not against Chairman Mao and Premier Zhou dancing. But dancing is, after all, dancing. Why must we set up a ‘Zhongnanhai Performing Arts Troupe’ just to dance with the Central Committee’s Chairman? All they do is bring in beautiful young ladies and lock them up in here for the whole day. The people will definitely curse if they come to know about this!” At the time almost all the highest-ranking officials were involved in extramarital affairs, Li Xiannian being no exception. He had a mistress with a background in nursing. Not only did she take good care of Li, she also bore his son.

Jiang finally realized, then, that it was either the birthday of Li’s mistress or son. He knew he had to do whatever it took to get a birthday gift to them. While it’s a given that the opinions of one’s sexual partner carry weight, this holds all the more so for those of a mistress. Jiang had dined with Li in hopes that he could talk about the Hu Yaobang situation, but now the matter of the birthday took precedence for Jiang. Jiang suppressed his vexation. As he ate, he inquired attentively about Li’s opinions on Hu. Upon understanding Li’s attitude towards Hu, Jiang told him that what he had said would benefit Jiang for life and assured him that he would follow Li’s instructions in handling things. Li was delighted. After dinner Jiang didn’t stay long. He had something more important to do.

After Jiang arrived home he sent his chauffeur off, claiming he had no further business to attend to. Jiang watched as the chauffeur drove off. When he was sure that the chauffeur could no longer see him, Jiang did not enter his home but, rather, sneaked off to buy a large birthday cake. It was getting late by that point, but Jiang, without the slightest hesitation, boarded a cab alone and headed back to the guesthouse. When Jiang reached the guesthouse he was told that Li Xiannian was attending to another guest. The guard however, remembering Jiang, invited him in. Jiang shook his head, though, and stood outside to wait. Jiang was worried others might discover what he was doing and follow suit; he wanted to be the only one who looked good.

As luck would have it, it was a bitterly cold and snowy night. Since Jiang was accustomed to having a chauffeur drive him to and from any destination, he wasn’t prepared for the weather and had only a thin overcoat on. Little did he expect, however, to wait in the cold for so many hours. He was trembling as he waited. The guards repeatedly asked Jiang in upon seeing that snow was gathering on his overcoat. But Jiang just smiled and didn’t respond, knowing that Li Xiannian and his mistress would be all the more impressed upon seeing Jiang’s coat covered in snow. Jiang thus stood in the snow, cake in hand, for a full four hours. Still, though, the guest did not exit. The guard attempted several times to talk Jiang out of waiting. Finally a disappointed Jiang left the cake with the guard and returned home.

When the guest finally left, the guard gave the cake to Li Xiannian. He told Li that Jiang had stood outside for several hours, his overcoat covered with snow. Li Xiannian was touched and said, “Young Jiang’s not a bad guy! There aren’t many people like that around nowadays!”

All of Jiang Zemin’s effort paid off. Not long after he became General Secretary of the CCP Central Committee, replacing Zhao Ziyang in the wake of the 1989 Tiananmen Massacre.

4. Hu Yaobang Steps Down

According to those present, at the Jan. 16, 1987, democratic-style meeting of Deng Xiaoping, Chen Yun, Peng Zhen, Bo Yibo, Wang Zhen and others, Hu Yaobang was forced to resign. That is, he was removed from office. When during the meeting Hu was forced to step down, he was shocked and speechless for some time. Even his long-time friends had betrayed him and called for his removal. He could see it quite plainly. Until the day he died, Hu would regret making at that meeting, against his will, “self-criticism” statements so as to preserve the supposed “unity” of the CCP. In the end he said, “Whether a person accomplishes things is unimportant, but he must be a decent individual.” After the meeting Hu broke down and wept openly, heartbroken by the betrayal of erstwhile friends he thought he could trust.

The CCP didn’t want a man with a conscience like Hu Yaobang. A man with a conscience was of no use to them. Whoever speaks up for the common people poses a threat to the CCP’s autocratic control over the nation. The political fates of Peng Dehuai, Hu Yaobang and, later, Zhao Ziyang testify to this fact. The CCP leaders value instead people who fawn over them, engage in double dealings, and show a ruthlessness in suppressing dissent. Thus it was that senior CCP leaders began considering Jiang Zemin for a higher position.

In October 1987, Rui Xingwen, the Secretary of the Shanghai Municipal Party Committee who was always at loggerheads with Jiang Zemin, finally left. Rui could be called a fervent supporter of reform, and he had close ties with the reform-minded Zhao Ziyang. Jiang Zemin, on the other hand, had for some time kept close company with the conservative old guard, and thus discriminated against Rui. The Shanghai Gang that Jiang formed went against Rui on all fronts and prevented him from carrying out his work. Zhao appointed Rui Secretary of the Central Committee Secretariat, hoping to dissolve the conflict; Rui thus served as Secretary of the Shanghai Municipal Committee for less than one term.

5. Jealous of Zhu Rongji

Even though Jiang Zemin formed a faction to take full control in Shanghai, citizens incessantly complained of hardship during his two years as mayor. In 1986 the market economy in many other areas of the country was doing well. While the rest of the country was happy to see at last an increased supply of goods, the people of Shanghai still had to use ration cards for many of their purchases.

The underlying reason for Shanghai’s market woes was none other than Jiang’s selfish desire to show off political “achievements.” In 1986, the Governor of Guangdong Province, Ye Xuanping, turned over to the central government provincial tax revenues of only 250 million yuan, while Shanghai Mayor Jiang turned over revenues of 12.5 billion yuan—a staggering 50 times the revenue of an entire province. The unreasonable act didn’t come free of consequences, though. In a mere two years the people of Shanghai were in such dire straits they couldn’t buy even the most basic and essential of items.

While Jiang was busy showering senior CCP leaders with praise and flattery, Deng Xiaoping had to address the serious problems Jiang had caused in Shanghai. Deng had to quickly make “Economic Czar” Zhu Rongji the mayor of Shanghai in order to clean up Jiang’s mess; Jiang was made Secretary of Shanghai’s Municipal Party Committee, a position requiring mere lip service and little real work. The CCP had in place at the time a “Mayoral Responsibility System” in which a mayor would be held to the things he said. All the same, Jiang’s poor performance in Shanghai—in sharp contrast to what his remarks had promised—did not prevent him from being promoted from membership in the Central Committee to membership in the Politburo of the Central Committee (at the 1st Plenary Session of the 13th CCP Central Committee in November 1987), thus making Jiang part of the CCP’s highest organ of state power.

Zhu Rongji was neither a descendant of senior CCP officials nor a martyr’s supposed foster child. He had less influence among the CCP’s inner circle than did Jiang Zemin. Moreover, he had once upon a time been branded a “rightist” during the anti-rightist campaign of 1957, the result of which was demotion and banishment to “reform through labor”—punishment which in effect knocked 20 years off of Zhu’s political career. One could argue, then, that Zhu Rongji’s rise had much to do with genuine abilities and charisma.

On April 25, 1988, Zhu Rongji spoke before more than 800 delegates from Shanghai. He wore a sharp, light-tan western suit and a red and black tie. According to the rules of the meeting, the Director and Deputy Director of the city-level People’s Congress Standing Committee, the Mayor and Deputy Mayors, and the candidates for the Director of the Supreme People’s Court and the Public Procurator General of the Supreme People’s Procuratorate could each speak for only 10 minutes, with a five minute cushion. Each speaker finished within 15 minutes. When Zhu began to speak the audience gave a thunderous applause. His lively remarks were met multiple times with resounding applause and affirmative laughter. Jiang Zemin, upon witnessing Zhu’s popularity, almost exploded in jealous rage. He was embarrassed by Zhu’s rapturous reception.

Jiang had little choice but to fake a smile. When others applauded, he would reluctantly clap once or twice. When the whole room was rocking with laughter, a forced grin could be made out. But a closer look suggested that Jiang would rather have cried. Jiang is by nature intolerant when it comes even to trivial matters—how could he possibly tolerate Zhu’s popularity? It was on that day that the seed of jealousy toward Zhu was planted in Jiang’s heart.

After Zhu became mayor of Shanghai he handled personally a great many small matters. For example, he insisted on reading letters written by ordinary citizens and made efforts to reply to those letters himself. Along with this he managed a great many larger affairs, such as relations with neighboring cities and provinces, the “Vegetable Basket Project,” addressing traffic problems, and the planning and development of Shanghai. Zhu once personally went to the upper reaches of the Huangpu River to try to solve its pollution problems and improve the quality of drinking water in Shanghai. His achievements and efforts won the hearts of the people.

Jiang Zemin paled in comparison to Zhu in these respects, and thus avoided mentioning Zhu’s achievements lest he give Zhu credit. The deputy mayors and bureau-level leaders who had it easy under Jiang had to now, under Zhu Rongji, prove their worth. Zhu has always had a rather unique countenance. But one stern look from him can strike fear or awe in a person. When he reprimanded deputy mayors and bureau-level leaders, though, it put them in an awkward position, and this in the presence of others. Shamed, those people lodged complaints with Jiang. Jiang seized the opportunity to severely rebuke Zhu, claiming that the mayor was breeding disunity out of a “strong ego.” Zhu had to endure the humiliation of doing self-criticism before bureau-level leaders.

In 1992 after a famed tour of southern China, Deng Xiaoping noticed that Jiang Zemin was resisting his program of political reform and opening-up to the outside world. Deng intended at the time to remove Jiang from office, but gave due consideration to the fact that he had already removed two secretaries general and that removing yet another might lead others to think poorly of him. Atop this, Jiang was tipped off as to Deng’s intentions by other Party veterans. Jiang was badly scared and made a 180-degree reversal by expressing to Deng his firm resolution as to implementing the reform and opening-up policy. After careful deliberation Deng decided to retain Jiang as General Secretary.

In April 1991, at the 4th Session of the 7th National People’s Congress, Zhu Rongji was elected Vice Premier of the State Council. On one occasion, Deng pointed at Zhu Rongji and said to Jiang Zemin, “I don’t know about economics, but he does!” Deng was in fact hinting to Jiang that he (Jiang) knew nothing of economics, unlike Zhu. In 1992 Zhu became a member of the Standing Committee of the Politburo of the Central Committee, China’s highest group of leaders. In 1998 Zhu was then appointed the fifth Premier of China. By that time the incompetent Jiang had been General Secretary, State Chairman, and Chairman of the Central Military Commission for nine years. Promoting 500 generals in a year was as if nothing to him.

6. Controlling the Media’s Domain at All Costs

While Jiang Zemin may be incompetent with real tasks, when it comes to boasting few are his match.

Jiang had come to understand the power of the media from his father, who engaged in traitorous propaganda work while serving under the Japanese authorities and Wang Jingwei’s puppet regime. Jiang thus devoted much attention to propaganda in the mass media. One maneuver Jiang made was to place members of his clique in the Department of Propaganda.

Many Shanghai publications are read all across China. So, senior leaders in the Central Party Committee saw the reports and could tell whether they were complimentary or critical of Jiang Zemin. After Jiang became mayor he paid special attention to the content of such media reports; sometimes he came across as almost paranoid. Outsiders might have viewed the World Economic Herald incident, which took place ahead of the Tiananmen Massacre, as unfortunate, but to Jiang Zemin it was just the natural thing to do.

One time the egotistical Jiang tried to show off his language skills at a press conference by using the English word “faces” to represent the Chinese word “mianmao” (appearances). The following day, the Liberation Daily dutifully substituted in its report the English word, “faces” with the Chinese “mianmao,” so that its readers could understand it. Jiang flew into a rage. He had wanted to show to all his proficiency in English, even though his usage of the word wasn’t quite right. He never imagined the media would, with but one stroke of the pen, deny him that pleasure. Jiang ordered his private secretary to call the Liberation Daily and voice his protest.

From the beginning of 1986 Jiang chaired all meetings with the Department of Propaganda of the Municipal Party Committee as well as meetings of the senior editors of all major Shanghai media. The routine became important for Jiang. In October of the same year, a fire broke out in a government building next to the Huangpu River. Reporters from Shanghai TV rushed to the scene and made a series of reports. Jiang felt that their prompt and uncensored reports were embarrassing, and was left enraged upon watching them. At a fire prevention meeting held one week later, Jiang chastised the Department of Propaganda, saying, “Such reports should not only caution people, but also inform them about the infrastructure problem in Shanghai and furthermore see that the problem has gradually improved.”

Another example was the meeting Jiang had with provincial People’s Representatives on May 4, 1987. Jiang learned that a water pipe near the new Shanghai Railway Station had been leaking water into the streets and left unattended for almost a year. A Representative had written several letters to the Zhabei District government, only to receive the same reply: “The problem is currently being rectified by the task-unit.”

Everybody knows that Jiang likes to make a show. As mayor he had taken charge of three projects in all—airports, wharves, and railway stations—each being, naturally, areas where he could draw the most attention. The water leakage at the new railway station would not only affect Shanghai’s image, but also, most certainly, affect that of Jiang himself. Jiang thus went in person to the local Water Supply Bureau and yelled at its workers, declaring, “Find someone to get that water pipe fixed!” The pipe was apparently fixed the very same day.

A few weeks later, journalist Xu Jingen of the Liberation Daily inquired with the Representative about the process of having the pipe fixed. He was told that Jiang had personally looked into the matter. Xu thought that it wasn’t befitting a mayor to personally get involved in such little things, and so he wrote an article, titled “The Flipside of Attending to Everything Oneself.” The piece, which ran in the People’s Daily on July 6, 1987, leveled harsh criticism against Jiang for giving such weight to a triviality like the pipe; normally something of the sort would be handled by the administrative management. The article wrote that, “It is most abnormal for leaders to get involved in every triviality. This can lead only to subordinate leaders developing habits of reliance and delay.”

Jiang was furious about the article. Though the article did not state Jiang’s name, it was undoubtedly referring to the highest level of Shanghai’s leadership. The innuendo at the conclusion of the piece drove Jiang simply mad. It said, “Some newspapers constantly run articles praising some mayors for solving the problem of exorbitant taxi fares, but if such things persist, won’t the director of the Price Bureau or the general managers of taxi companies become redundant?”

Jiang couldn’t stand being mocked on the front page of the Party’s most authoritative newspaper. Thus a special meeting was held on July 10 and attended by all CCP administrative officials serving in the propaganda and media organizations of Shanghai. Jiang, pounding the table fiercely with his fist, barked, “Xu Jingen hasn’t got the slightest idea of how to manage this city. That writer thinks he’s so great. I think he should step out of his office a little more often and look around!” The editors from the Liberation Daily who attended the meeting felt uneasy and lowered their heads. The meeting ultimately became a forum for attacking and blaming Xu and his superiors for the report. If that was not enough, Jiang soon “rectified” and reorganized the media: editors-in-chief and managers who had a history of truthful reporting were all removed. From that point on no media in Shanghai dared to comment on Jiang Zemin.

From The Epoch Times