The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has allowed scientists to gain a new understanding of supermassive black holes and the heat source of the dense clouds of gas and dust that surround them.

Using images and data collected by the JWST, a team of international scientists, led by researchers at Newcastle University, UK, found evidence that contradicts previously theorized understandings about these mysterious celestial objects.

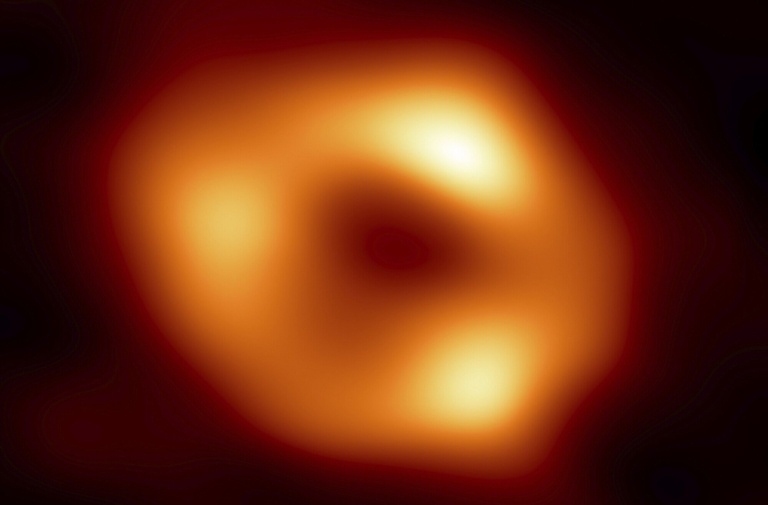

Black holes are understood to be collapsed stars of extreme density, with a gravitational force so strong that nothing, not even light, can escape it. Supermassive black holes are the largest category, with a mass millions or even billions of times greater than that of our sun.

Astronomers believe nearly all galaxies have these giant black holes at their center. Our Milky Way also has a supermassive black hole at its center.

The team pointed the JWST, the most powerful telescope-in-orbit ever made, at ESO 428-G14, a galaxy 70 million light years away. At its core is an “active galaxy nucleus” (AGN)—a black hole emitting powerful radiation along the entire electromagnetic spectrum, from X-rays and visible light to infrared light and radio waves.

The team analyzed the swirling cloud of dust and gas surrounding the black hole and found that the energy heating its gaseous torus does not originate from the black hole itself, as previously understood, but that intense jets of radio-wave emissions “shock” the dense gas and dust clouds at near-light-speeds, causing intense heating.

These shocks send jets of gas and dust flying well beyond the galaxies’ scope.

The study and its surprising conclusions were published on Tuesday in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, an authoritative science journal affiliated with Oxford University.

“There is a lot of debate as to how AGN transfer energy into their surroundings. We did not expect to see radio jets do this sort of damage. And yet here it is!” said David Rosario, a senior lecturer at Newcastle University and co-author of the study.

Given their high gravitational pull, supermassive black holes collect thick clouds of dust and gas around themselves on which they feed; but these clouds effectively obstruct observers’ view from the earth, complicating observation.

The JWST, which was put in orbit less than three years ago—in December 2021, to be precise—has high-resolution infrared capabilities that allow people to look through these clouds for the first time with significant detail.

With the telescope, the Galactic Activity, Torus, and Outflow Survey (GATOS) was launched, a research project dedicated to investigating these gaseous toruses surrounding black holes.

The research team was led by Houda Haidar, a doctoral student in the School of Mathematics, Statistics and Physics at Newcastle University.

“Having the opportunity to work with exclusive JWST data and access these stunning images before anyone else is beyond thrilling,” she said in a press release. “I feel incredibly lucky to be part of the GATOS team. Working closely with leading experts in the field is truly a privilege.”

The findings constitute a significant step toward understanding galaxies’ life cycle, the researchers said.

“We are learning how galaxies recycle their material, which ultimately helps us understand the processes by which supermassive black holes influence galaxies, including our own.”