Pregnancy-related deaths have returned to pre-pandemic levels, according to federal data.

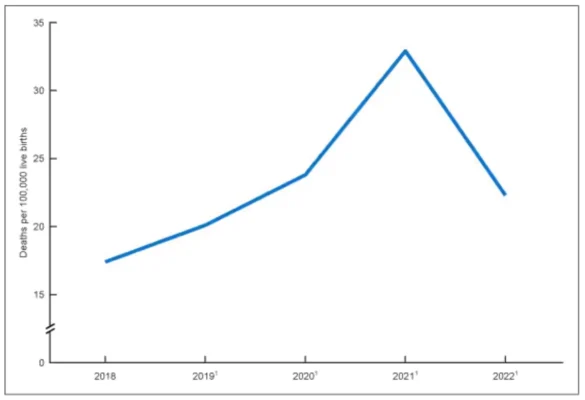

In 2022, 817 women died of maternal causes in the United States, compared with 1,205 in 2021, 861 in 2020, 754 in 2019, and 658 in 2018, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

On Thursday, the agency released a report detailing the final maternal mortality data for 2022. It also recently released provisional data for 2023.

The provisional 2023 data show that the number of deaths is probably similar to years 2019 or 2018. The finalized data may differ a lot from the provisional, as in 2022 the difference was 10 percentage points higher in the final data.

The maternal mortality rate for 2022 decreased to 22.3 deaths per 100,000 live births, compared with a rate of 32.9 in 2021.

There were about 19 maternal deaths for every 100,000 live births in 2023, according to the provisional data. That’s in line with rates seen in 2018 and 2019.

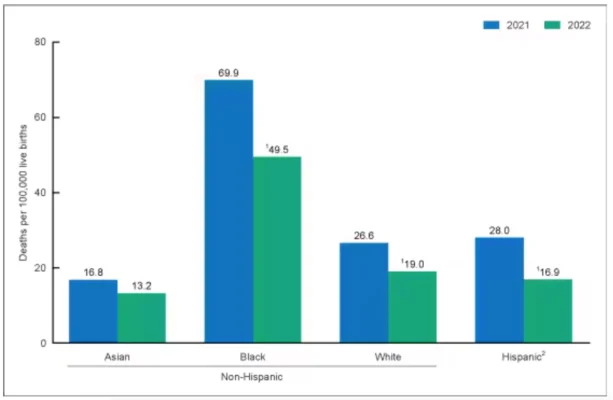

But racial disparities remain: The death rate in black mothers is more than two-and-a-half times higher than that of white and Hispanic mothers.

Donna Hoyert, a CDC maternal mortality researcher, suggested that COVID-19 was a possible cause of decreased deaths in 2023.

COVID-19 can be particularly dangerous to pregnant women. And, in the worst days of the pandemic, burned out physicians may have added to the risk by ignoring pregnant women’s worries, experts say.

Fewer death certificates are mentioning COVID-19 as a contributor to pregnancy-related deaths. The count was over 400 in 2021 but fewer than ten last year, Ms. Hoyert said.

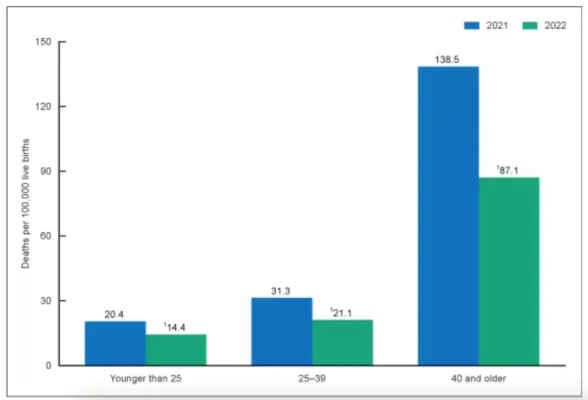

Age is one of the biggest factors, with women over 40 experiencing many more problems compared to women aged 25-39 and women aged below 25.

In 2022, deaths in the group of women over 40 (87 deaths per 100,000 women) were around four times higher than the 25-39 group (21 per 100,000) and six times higher than the below 25 group (14 per 100,000).

The CDC counts women who die while pregnant, during childbirth, and up to 42 days after birth from conditions considered related to pregnancy. Excessive bleeding, blood vessel blockages, and infections are the leading causes.

“In the last five years we’ve really not improved on lowering the maternal death rate in our country, so there’s still a lot of work to do,” said Ashley Stoneburner, the March of Dimes director of applied research and analytics.

The advocacy organization this week kicked off an education campaign to get more pregnant women to consider taking low-dose aspirin if they are at risk of preeclampsia—a high blood pressure disorder that can harm both the mother and baby.

Other efforts may be helping to lower deaths and lingering health problems related to pregnancy, including stepped-up efforts to fight infections and address blood loss, said Dr. Laura Riley, a New York-based obstetrician who handles high-risk pregnancies.

Maternity units are reportedly on the decline in hospitals due to a decrease in staffing and low birth rates, leaving many in rural communities to have to drive up to 45 minutes to be served.

According to a 2022 “Maternity Care Deserts Report” conducted by March of Dimes, in areas of the United States where there is little or no access to maternity units, almost 6.9 million and up to 500,000 births are impacted, including a 5 percent increase in counties that have reduced their access since 2020.

In maternity-care deserts, somewhere around 2.2 million women and up to 150,000 babies are impacted.

In the UK, research on mothers from 2020 to 2022 showed that blood clots were the leading cause of pregnancy-related deaths.

It is widely known that pregnancy and the birth-control pill place women at increased risk of suffering from blood clots.

The COVID-19 vaccines, too, have caused blood clots in some people, with young people reportedly at greater risk.

The AstraZeneca jab was withdrawn in many countries, including the UK after the link to clotting was widely reported. It was first withdrawn for the under-40s in the UK before the government eventually stopped recommending COVID-19 vaccinations for all healthy people under 50.

The Associated Press, Matt McGregor, and Rachel Roberts contributed to this report.